Fisheries and Coastal Communities

Climate change may seem far off in the future to some people, but for many who work in fisheries, it’s definitely here and it’s already having a big effect.

Changes in water temperature and chemistry are leading to shifting abundances and distributions of several fish species. Commercially valuable species—such as silver hake, American lobsters, and winter flounder—are moving farther north or into deeper waters to stay within their preferred temperature ranges. Warmer temperatures can also influence growth rates and the timing of seasonal migrations. In 2012, lobsters in the Gulf of Maine started their summer migration a month early and grew to market size faster than usual. The result was a saturated market and a price collapse for Maine lobstermen. (See the related Case Study Maine's Lobster Fishing Community Confronts Their Changing Climate.)

Similar changes are happening in many places along our coasts. In communities that depend on fishing and tourism, these changes can cost jobs and disrupt traditional ways of life. These impacts highlight the need for information and tools to help track climate-related changes, understand the mechanisms of change, and ultimately provide fisheries managers and stakeholders with forecasts and early warnings of environmental changes in marine and coastal ecosystems.

Given the pace and scope of expected climate impacts on marine, coastal, and freshwater ecosystems, the ability to understand, plan for, and respond to climate impacts on fisheries and the communities that depend on them is fundamental to their stewardship in a changing climate.

The preceding text was adapted from the NOAA Technical Memorandum NOAA Fisheries Climate Science Strategy.

Communities

Coastal communities occupy less than 10 percent of the land area in the United States, but they are home to over 39 percent of the country’s population. The communities contribute 51 million jobs to the economy and 45 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product.1

The impacts of climate change on tourism and recreation are expected to vary significantly by region. For instance, some of Florida’s top tourist attractions, the Everglades and Florida Keys, for instance, are threatened by sea level rise. These regional economies may see revenue losses of $9 billion by 2025 and $40 billion by the 2050s. Meanwhile, in more northerly regions such as coastal Maine, tourism may increase as summer months grow warmer and more people decide to visit the state’s beaches.2

Some components of the marine ecosystem are already responding to changes in their environment. Warmer ocean conditions along the East coast coincide with changes in distribution and abundance of some of the nation’s living marine resources. For example, the distribution of black sea bass populations has shifted to the north: these fish have increased in abundance in the Gulf of Maine at the same time as their abundance decreased in the historically fished areas off the coast of North Carolina.

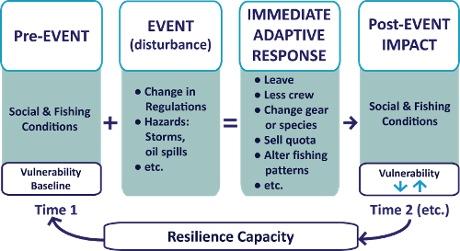

NOAA Fisheries Economics & Human Dimensions Science Program has developed a systems-thinking model to characterize vulnerability and resilience in fishing communities. The following example illustrates one way that changing fish distributions can affect a fishing community.

An example of community response to change

- Pre-Event: Imagine a thriving fishing community that is highly dependent on a single species of fish. The strong sense of community among people is obvious from measures such as high participation in events—such as periodic fish fries and an annual fish festival.

- Event: A new stock assessment indicates that the primary fish species on which the community depends is being overfished. The fishery management council responds by reducing the Annual Catch Limit (ACL) by 100,000 pounds.

- Immediate Adaptive Response: The reduction in catch limit causes several vessels to reduce the sizes of their crews. One person sells his vessel and one fish house closes.

- Post-Event Impact: In the wake of these changes, community members no longer organize fish fries and insufficient numbers of people are available to work the annual fish festival. These losses reduce the level of funds the local fishing organization has to lobby for guidelines that could keep them profitable. Several families choose to move away, and the community’s social networks weaken as key people are no longer available to lend their leadership or support for common concerns.

- The Bottom Line: A range of factors can initiate a negative effect on the community’s capacity for resilience, increasing vulnerability, or decreasing the community’s ability to address future disruptions. Fishery regulations were the instigating event in this case, but disturbances in many other aspects of the economy can disrupt a community’s social networks.

Representing the sequence of events in a conceptual model can help communities perceive opportunities to intervene in ways that build their capacity for resilience. The generalized model can be applied to any coastal community that experiences a natural or man-made disruption.

The previous text is excerpted and abridged from the NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service Socioeconomics Topic.

- 1. NOAA National Ocean Service, 2016: Ocean Facts: What percentage of the American population lives near the coast? Accessed June 20, 2016.

- 2. Hales, D., W. Hohenstein, M. D. Bidwell, C. Landry, D. McGranahan, J. Molnar, L. W. Morton, M. Vasquez, and J. Jadin, 2014: Ch. 14: Rural Communities. Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment, J.M. Melillo, Terese (T.C.) Richmond, and G.W. Yohe, Eds., U.S. Global Change Research Program, 150–174. doi:10.7930/J02Z13FR.

Public domain photo by VladUK, via Wikimedia Commons