High-Tide Flooding

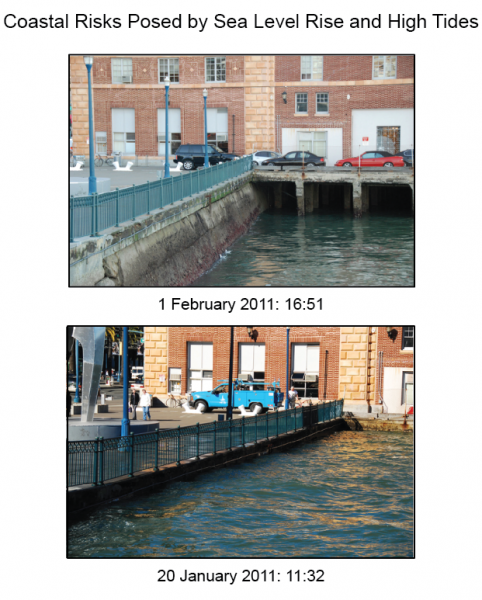

During extremely high tides, the sea literally spills onto land in some locations, inundating low-lying areas with seawater until high tide has passed. Because this flooding causes public inconveniences such as road closures and overwhelmed storm drains, the events were initially called nuisance flooding. To help people understand the cause of these events, they are now referred to as high-tide floods.

High-tide flooding is generally very localized, occurring at a scale of city blocks. By definition, a high-tide flooding event occurs when local sea level temporarily rises above an identified threshold height for flooding, in the absence of storm surge or riverine flooding. The heights of locally identified flooding thresholds are related to impacts such as standing water on low-lying roads or seawater entering stormwater systems.

Recently, sea level experts at NOAA looked at existing flood thresholds and found a pattern in the thresholds based upon tide range. They applied that pattern nationwide to develop a consistent way to monitor minor, moderate, and major high-tide flooding, even at locations without tide gauges. Documenting these floods using consistent methodology gives NOAA a way to communicate the increasing frequency of high-tide flooding to the public.1

When coastal storms coincide with high tides, the depth and extent of coastal flooding can increase dramatically. Even relatively weak winds blowing toward land during high-tide events can push huge volumes of water inland. Rainfall can also add a substantial volume of water to high-tide floods.

Extreme high tides

Tides that are much higher than usually occur a few times per year during new and/or full moons. These perigean spring tides—also known as king tides—are astronomical in origin: they occur when the Moon's regular orbit brings it to its closest distance to Earth (called perigee) during a new or full moon, when the Earth, Moon, and Sun are in a straight line. The combined gravitational force of the Moon and Sun on the Earth's oceans results in the higher-than-usual tide level. Checking NOAA's Annual State of High-Tide Flooding and Outlook or the Tides and Currents Seasonal Bulletin to learn when perigean spring tides will occur in the next year, and then raising public awareness of potential flooding before it occurs, is a step toward resilience.

Astronomical alignments are not the only factor affecting the height of tides. High-tide flood frequencies vary year-to-year due to large-scale changes in weather and ocean circulation patterns, such as during the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO). During the El Niño phase, high-tide flood frequencies on the U.S. West and East Coasts were amplified above local trends at about half of the locations examined in a recent NOAA study.1 This predictable ENSO response may better inform annual budgeting in some flood-prone locations for emergency mobilizations and proactive responses.

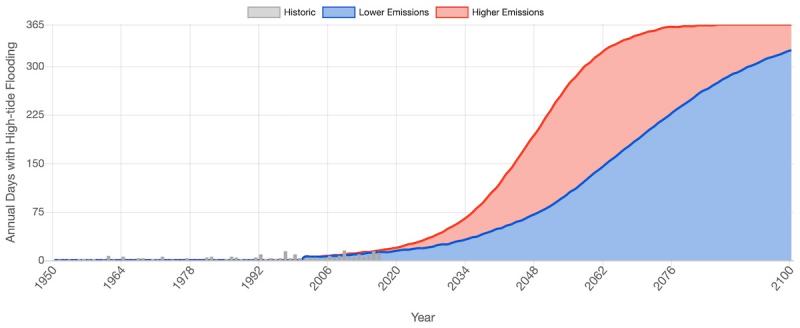

High-tide flooding is already forcing some East Coast cities to install costly pump stations to clear floodwaters from the streets. And as global sea level rises, high-tide flooding will become more frequent and severe. By the year 2100, high tides are projected to occur on top of another 1 to 8 feet of sea level rise.2,3 In other words, coastal water levels we view as floods today will become the new normal for high tides in coming decades.

- 1a1bSweet, W., G. Dusek, J. Obeysekera, and J. Marra, 2018: Patterns and Projections of High Tide Flooding Along the U.S. Coastline Using a Common Impact Threshold. NOAA Technical Report NOS CO-OPS 086. 56 pp.

- 2Sweet, W.V., R.E. Kopp, C.P. Weaver, J. Obeysekera, R.M. Horton, E.R. Thieler, and C. Zervas, 2017: Global and Regional Sea Level Rise Scenarios for the United States. NOAA Technical Report NOS CO-OPS 083. NOAA/NOS Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services. 75 pp.

- 3Sweet, W.V., R. Horton, R.E. Kopp, A.N. LeGrande, and A. Romanou, 2017: Sea level rise. In: Climate Science Special Report: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume I [Wuebbles, D.J., D.W. Fahey, K.A. Hibbard, D.J. Dokken, B.C. Stewart, and T.K. Maycock (eds.)]. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA, pp. 333-363, doi: 10.7930/J0VM49F2.