Relocation

Climate-related impacts are forcing the relocation of tribal and indigenous communities, especially in coastal regions. These relocations, and the lack of governance mechanisms or funding to support them, are causing loss of community and culture, health impacts, and economic decline.

Relocation may be nothing new to indigenous peoples, as many were migratory based on location of needed resources prior to the arrival of Europeans to the Western Hemisphere. However, member of Tribal Nations living in or near Indian reservations today—often on marginal lands—have limited choices, especially when changes to their land base become so severe that staying in place is no longer an option. When there are not any, or only less desirable, options left for in-place adaptation, some tribal communities are proactively working to relocate as a community to maintain their cultural sovereignty, rights, and integrity, and to do so with dignity.

Relocation places added pressures on the communities in order to preserve and maintain traditional values and lifestyles. Some tribes have repeatedly struggled with the serious consequences of relocation on their communities. For example, many eastern and southeastern tribal communities were forced to relocate to Canada or the western Great Lakes in the late 1700s and early 1800s, and later to Oklahoma. This required them to adjust and adapt to new and unfamiliar landscapes, more limited subsistence resources, and different climatic conditions. Forced relocations have continued into more recent times, and have proven to be more untenable with the cascading effects of changing climate.

Many native communities in Alaska and other parts of the coastal United States are now facing relocation once again as a consequence of climate change and other stressors, including food insecurity, unsustainable development, and extractive practices on or near traditional lands. Such forms of displacement are leading to severe impacts on the livelihood, health, and culture of native communities.

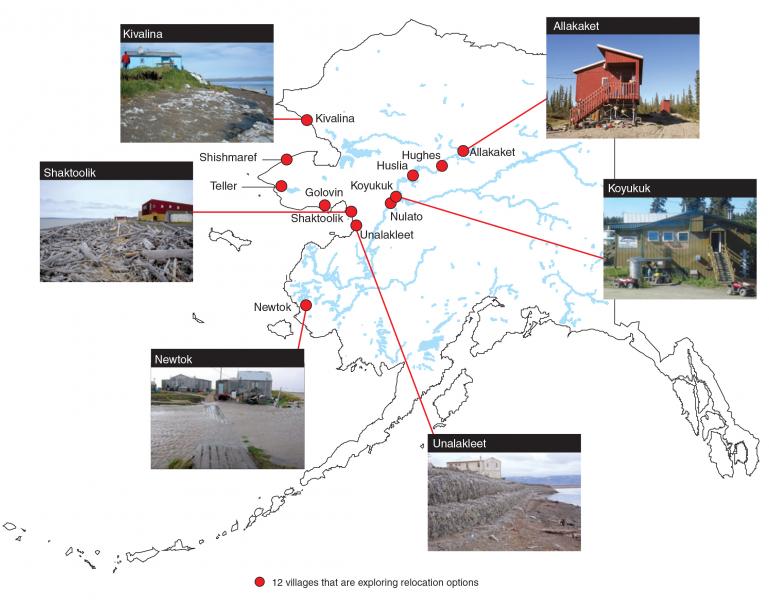

- In Arctic Alaska, the summer sea ice that once protected the coasts has receded, and autumn storms now cause more erosion, threatening many communities with relocation. For example, Newtok—a traditional Yup’ik village in Alaska—is experiencing accelerated rates of erosion caused by the combination of decreased Arctic sea ice, thawing permafrost, changing storm patterns, and unprecedented extreme weather events. Over 30 other Alaska Native villages are either in need, or are already in the process, of relocating their entire village.

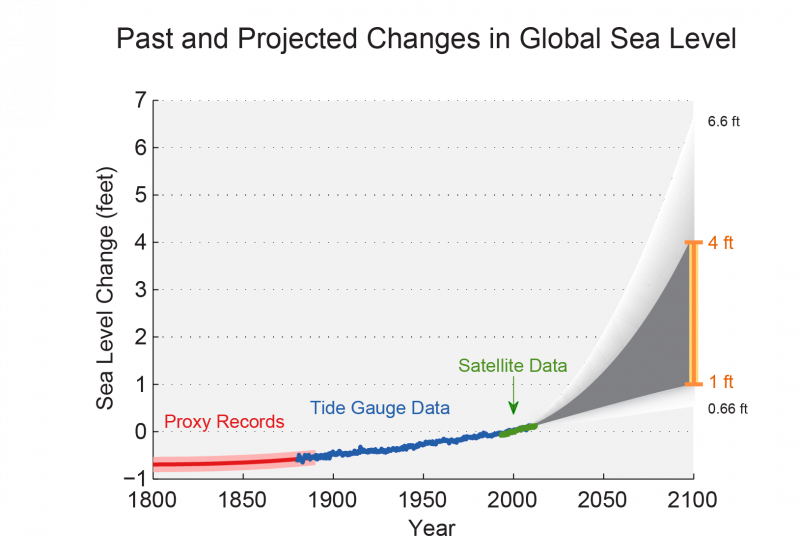

- Tribal communities in coastal Louisiana are experiencing climate change-induced rising sea levels, along with saltwater intrusion, subsidence, and intense erosion and land loss due to oil and gas extraction and to levees, dams, and other river management techniques, forcing them to either relocate or try to find ways to save their land.

- Tribal communities in Florida are facing potential displacement due to the risk of rising sea levels and saltwater intrusion inundating their reservation lands.

- The Quileute tribe in northern Washington is responding to increased winter storms and flooding connected with increased precipitation by relocating some of their village homes and buildings to higher ground within 772 acres of the Olympic National Park that has been transferred to them; the Hoh tribe is also looking at similar options for relocation.

Currently, institutional frameworks do not readily support relocating entire communities. Many national, state, local, and tribal government agencies lack the technical, organizational, and financial capacity to implement relocation processes for communities displaced by climate change. New governance institutions, frameworks, and funding mechanisms are needed to specifically respond to the increasing necessity for climate change-related relocation. To be effective and culturally appropriate, it is important that such institutional frameworks recognize the sovereignty of Tribal Nations and that any institutional development stems from an equitable partnership with indigenous representatives.

The preceding text was excerpted and adapted from the report Climate Change Impacts in the United States: The Third National Climate Assessment (Chapter 12: Indigenous Peoples, Lands, and Resources and Chapter 22: Alaska) and from the United States Government Accountability Office report Alaska Native Villages: Limited Progress Has Been Made on Relocating Villages Threatened by Flooding and Erosion (2009).