Adjusting to rapid melting

Nuiqsut is a traditional Inupiat community located in Alaska's North Slope region on the west bank of the Colville River, 18 miles south from the inlet to the Beaufort Sea. The surrounding landscape is largely flat and treeless, covered with tundra vegetation and dotted with hundreds of lakes. Nuiqsut residents recall the lessons of their elders, who spoke of a time to come that would bring warming and hardship.

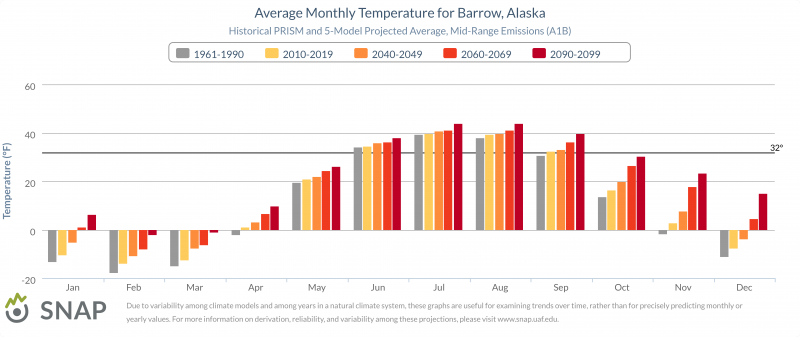

The North Slope of Alaska is well within the Arctic Circle—even during its short summers, the land there is mostly permafrost and ice. People, wildlife, and vegetation in the region have all adapted to live in the cold, mostly frozen environment. However, as temperatures warm across the region, the environment is changing rapidly, and a new Arctic is emerging. The new environment is characterized by thawing land, open water instead of ice-covered lakes and ponds, and a longer warm season.

For residents of the North Slope, this means new challenges in building and maintaining infrastructure, providing local services, collecting food and water, and navigating safely over land and sea. It also means new opportunities for subsistence, land use, transportation, commerce, and development. Understanding the local effects of changing conditions is the first step in finding a healthy course through the challenges ahead.

Food safety and food insecurity

In addition to threats to native plants and wildlife, warming conditions can also cause traditional underground ice cellars to melt. These cellars are cut directly into the permafrost to store food. When the permafrost melts, the hard-won caribou, seal, and other meat stored in these cellars can rot and become unusable. This compounds two other problems with these traditional food sources: the animals have grown more scarce, and collecting them has become more difficult and dangerous because of melting sea ice and flooded lands.

In these changing conditions, some people are experiencing issues of food insecurity. According to a survey of North Slope Borough communities conducted in 2010, over 20 percent of households experienced times when they did not have enough food. Of the households that reported difficulty getting the food needed to eat healthy meals, 51 percent of Inupiat heads of household reported that this was because they could not get enough subsistence foods. Loss of adequate food storage affects food security, and also raises concerns about food-borne illnesses.

New risks to the whale harvest

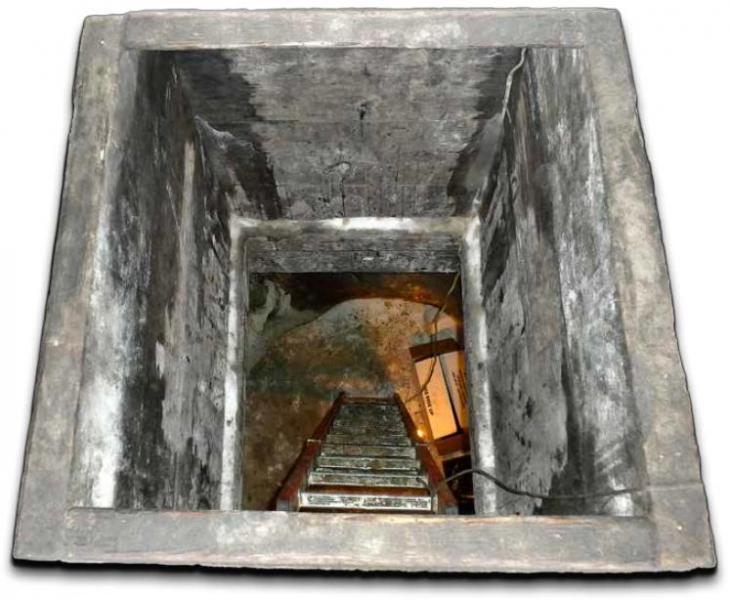

In the spring and fall each year, George Adams and his six-man crew hunt bowhead and beluga whale in the coastal waters of the Beaufort Sea near Barrow, Alaska. Adams, the whaling captain, and his crew divide the harvested whale meat and blubber and store it in traditional ice cellars, called siġluaqs. These underground cellars are dug into the permafrost and framed with whalebone and driftwood; they provide a year-round freezer for the whale meat and maktak—whale blubber and skin. Over the cellars, driftwood poles are arranged like a teepee; they hold a block pulley used for raising and lowering whale meat and blubber into the cellars below.

Adams' family has relied upon their cellar for generations. Even in summer, they could descend into the icy, earthen room and retrieve frozen food for their dinner. But in January of 2010, Adams opened the cellar door and found water on the floor. Despite outside temperatures below 0°F, the interior of the cellar was well above the freezing point. The stored food was not frozen, but wet and beginning to mold. For the first time in over 100 years, the cellar had failed.

As ice cellars thaw, the Inupiat are increasingly at risk for food-borne illness, food spoilage, and even injury from structural failure. Climate change is disrupting the traditional Iñupiat food system and creating a new safety risk.

Ice cellar safety and function

Ice cellars offer convenience, ample space, and an economical method for refrigeration. As a result, they are in use in the communities of Nuiqsut, Kivalina, Point Hope, Point Lay, Barrow, Wainwright, and Kaktovik. However, across the North Slope, people are documenting problems with preservation and storage of subsistence foods in these cellars. For instance, overly wet or warm conditions can prevent proper air drying of fish, caribou, and seal. Permafrost thaw and erosion can ruin food and damage or prevent use of the cellars. Some ice cellars continue to function effectively, but some cellars are in trouble. Some cellars have collapsed due to erosion, while others are operating on the margins of safety, vulnerable to further warming. Ice cellars built in the 1970s started showing increasing problems with thawing and caving in the late 1980s and 1990s.

Understanding the construction, operation, status, and challenges for ice cellars is important for both food security and for safety. In April 2014, an inventory of Nuiqsut ice cellars revealed that seven ice cellars were in use. The inventory showed that those located nearest to the river were warming and, in some cases, filling with water. Residents have also observed that warmer air and soil temperatures have lengthened the time it takes to freeze the stored whale meat and maktak. Some adaptations have been applied in the cellars to prevent spoilage: one elder was using a convection fan to keep maktak fresh through the summer. Historically, though, it has been cold enough to keep many foods in the entryway of homes well into spring—a practice that is often no longer possible due to the warming conditions. Additionally, the timing and availability of snow used to clean out ice cellars in the spring is another problem. In recent years, there has often not been snow available for this task.

Investigating options for adaptation and resilience

Understanding conditions inside cellars and the factors that affect them is critical for determining adaptation options and for building the communities' resilience to the warming conditions. One way to start is by identifying good local cellars that store food safely and preserve the food's taste. Experts have recommended monitoring humidity and temperature in successful cellars to see how they change throughout the food storage season. They could then seek to replicate these conditions in new cellars or in engineered storage facilities.

Experts are calling for immediate action to address cellar safety issues and prevent serious injury or death. They recommend the development of guidance practices for ice cellars, addressing such topics as structural issues, confirmed space, air quality, and slip/fall procedures.

Since many of the cellars are still in use, the priority is on finding ways to prevent them from thawing and to develop storage for community members who are without cellars. To address the growing issue of food insecurity—and to ensure physical safety and the safety of food in local ice cellars—the Nuiqsut community is investigating several options for adaptation:

-

Improving the storage environment in existing cellars,

-

Establishing new cellars in a location with a more conducive environment, or

-

Developing alternative methods for food storage.

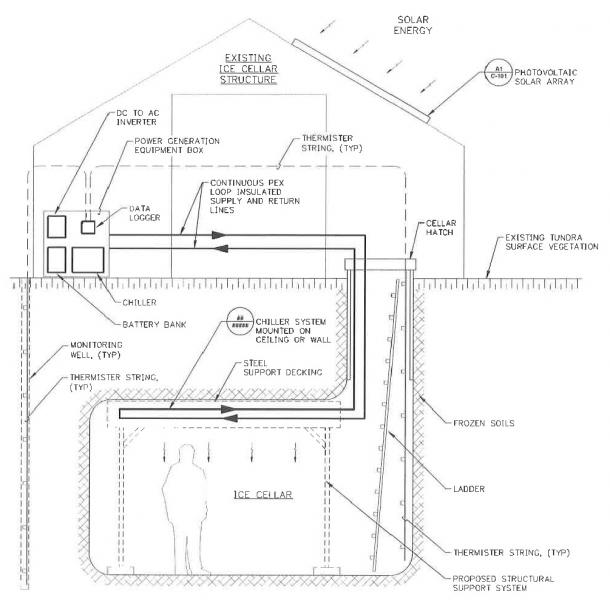

A possible engineered solution

Engineers at the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (ANTHC) have developed a conceptual design for an ice cellar featuring an energy-efficient, thermostat-controlled cooling system, a solar- and/or wind-energy power system, and structural supports and ventilation for allowing exchange of cellar and outside air. The design is based on technology being piloted in other communities to protect permafrost-vulnerable water and sanitation infrastructure. Designs like this may someday be used to improve food storage for North Slope communities.