The gap in knowledge

As a changing climate increases the vulnerability of assets in the Great Lakes region, cooperation among community groups and municipal officials becomes essential to the process of identifying and responding to impending challenges. However, varying motivations and priorities among these groups can be obstacles to working together.

Despite rising concerns of climate impacts, formal plans and actions for adapting to a changing climate remain rare in the Great Lakes region. In 2015, only Marquette and Grand Rapids in Michigan and Dane County and Milwaukee in Wisconsin had developed formal climate adaptation plans. And as of 2018, none of the plans have been implemented. Furthermore, a study of people from Great Lakes cities found that fewer than ten percent of them could identify a public official whom they perceived was pushing for climate action.

The obvious gap between increasing needs for climate adaptation and leaders who are eager to address the issue was one factor keeping things from moving forward.

Boundary organizations provide social glue

In 2015, a group of local government staff and their partners recognized the need for a bridging organization that could connect communities with researchers and adaptation resources. The group applied for and received grant funding through the Urban Sustainability Directors Network (USDN).

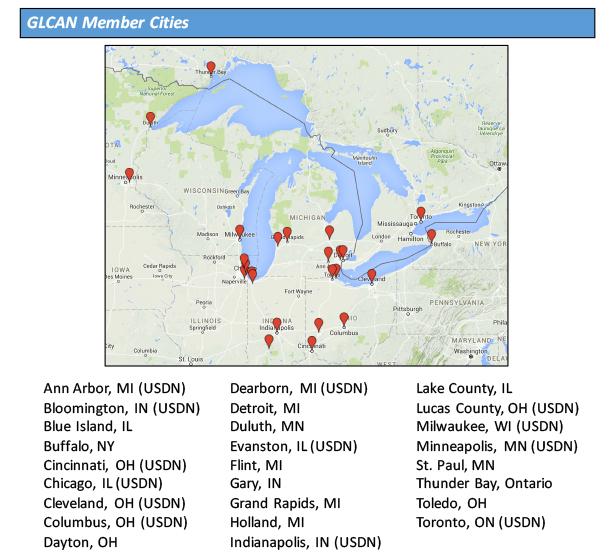

Today, they are a member-driven peer network known as the Great Lakes Climate Adaptation Network (GLCAN), and they work together to explore and act on climate adaptation challenges in the Great Lakes region. Membership is limited to local government staff and partners in the Great Lakes region.

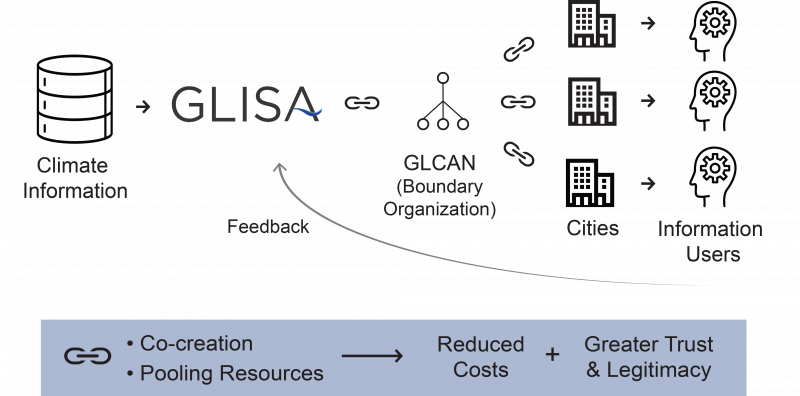

GLCAN also works with Great Lakes Integrated Sciences + Assessments (GLISA), a NOAA-supported program at the University of Michigan and Michigan State University. Both boundary organizations work together to find and deliver climate information to support member-cities in their decision making.

Putting boots on the ground for assessment

With funding from the USDN Innovation Fund, GLCAN helped the cities of Ann Arbor, Dearborn, Evanston, Indianapolis, and Cleveland assess their vulnerabilities to climate change impacts. With additional funding from GLISA, the group is collaborating with the Huron River Watershed Council to develop vulnerability assessments for city budgeting and planning across the region. The assessments can help cities identify and reduce vulnerabilities to anticipated climate impacts such as extreme heat and rainfall events.

Based in part on this work, the USDN has also funded a follow-up project for GLISA. Working with the non-partisan research group Headwaters Economics, GLISA will work with more Great Lakes and Mid-Atlantic cities to develop a socioeconomic mapping tool for climate risk planning.

Tangible benefits of boundary organizations

Organizations such as GLCAN and GLISA can help build bridges for knowledge transfer between scientists and decision makers. Their functions can also traverse the boundaries between science and policy by spanning the range between the production of climate information and the use of that knowledge.

Results from the organizations’ community interactions show that the linking boundary chain such as that illustrated in the figure above can increase local scientific knowledge, encourage new cities to participate in climate adaptation activities, reduce costs by increasing efficiency, and help cities better prepare for changing conditions.