Display Image

Region

Northern Great Plains

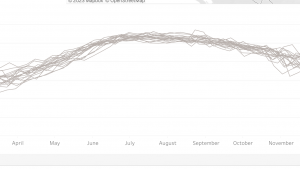

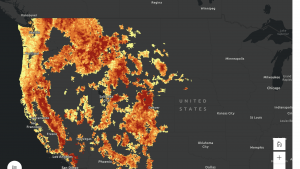

The Northern Great Plains is experiencing unprecedented climate-driven extremes, including severe drought, floods, and wildfires. These changes threaten economic sectors such as agriculture and recreation and affect the health, well-being, and livelihood of the region’s residents.

Title

Key Messages

Text

- Climate change is compounding the impacts of extreme events

- Human and ecological health face rising threats from climate-related hazards

- Resource- and land-based livelihoods are at risk

- Climate response involves navigating complex trade-offs and tensions

- Communities are building the capacity to adapt and transform

Key messages adapted from the Northern Great Plains chapter of the Fifth National Climate Assessment.

Image

Looking for previous content for the Northern Great Plains region?

Related Case Studies & Action Plans

Image

Diane Larson/USGS

Image

Bureau of Reclamation Research and Development Office

Image

Elissa Chott/National Wildlife Federation