Indigenous Peoples

Key Points:

- Indigenous peoples of the Northern Great Plains are at high risk from a variety of climate change impacts, especially those resulting from hydrological changes. These include changes in snowpack, disruptions in seasonality and timing of precipitation events, extreme flooding, droughts, melting glaciers, and reduction in streamflows.

- Climatic changes are already resulting in harmful impacts to tribal economies, livelihoods, and sacred waters and plants used for ceremonies, medicine, and subsistence.

- Many native nations have been very proactive in adaptation and strategic climate change planning, but like any sovereign government the scale and the scope depends on a variety of factors.

- Collaboration, coordination, and support across local, state, and federal entities is key for native nations to address climate change impacts.

“Tribal nations” and “native nations” are often used interchangeably to describe sovereign Indigenous governments in the region. “Indigenous peoples” and “tribal communities” are also used to describe people of Native American ancestry living on and near sovereign tribal lands in the Northern Great Plains.

1) Climate change impacts

Indigenous peoples of the Northern Great Plains have a unique and distinct connection to the land, often dating back thousands of years, and Indigenous inhabitants in the region are observing many climate and seasonality changes to their natural environment and ecosystems that are impacting livelihoods. Climate impacts have led to reduced access to subsistence and traditionally harvested species, including wildlife and plants used in the practice of sacred ceremonies and traditional medicines. This negatively impacts traditionally practiced cultural lifeways tied to the sacredness of land and water, affecting the overall health and well-being of the Northern Great Plains’ Indigenous peoples. (For more information, read the case study Crow Nation and the Spread of Invasive Species in the Fourth National Climate Assessment.)

Tribal elders and natural resource managers in the region have observed seasonal changes in water cycles, phenology (periodic biological responses, such as plant flowering), bird migrations, and hibernation cycles, as well as the reduced availability to harvest traditional plant-based foods, all while witnessing a significant decline in native tree species such as conifers and hardwoods.

Negative impacts of a warming climate have likewise affected subsistence fisheries and the overall riparian (wetlands adjacent to rivers and streams) ecosystem health, including declines in salmon, trout, frogs, and mussels due to reduced streamflow and increased water temperatures. Extreme heat and declines in traditional plants such as sage, cottonwoods, and cattails are already impacting sacred ceremonies such as the Sundance, when participants pray while fasting within a constructed lodge lined on the outside with cottonwood saplings used for shading the dancers during a three- or four-day event.1

Many regional tribal communities are experiencing increased fire frequency and intensity. Climate projections that show increased fire risks for the region may result in reduced succession rates of forests, impacting wildlife, freshwater systems, and fisheries and posing a significant threat to the health of tribal communities.

A warming climate poses the greatest threat to water quality and quantity across regional tribal nations. Water is considered a spiritual being, defining traditional cultural connections through sacred ceremonies as well as supporting local economies for tribal communities that transcends the western science view as a consumptive commodity. Water is integral to defining the health and cultural expression of tribal nations, particularly given the impacts of increased temperatures that have led to extreme weather events, either in the form of extreme flooding or prolonged droughts, reduction or changes in snowpack, and seasonal timing of precipitation events. These climate sensitivities, along with substandard water infrastructure, pose considerable threats to tribal sovereignty related to water rights, resulting in water usage insecurity.

In the Northern Great Plains, just under 29,000 (76 percent) of Indigenous households are in need of new or improved sanitation facilities, and approximately 5,000 households lack access to safe water supplies and sewage facilities. The total cost to remediate sanitation facility deficiencies in the region was estimated at $280 million, according to a 2015 annual report from the Indian Health Service. Climate change is exacerbating the problem of water supply disruptions due to decreased water availability, as happened in 2003 when the entire Standing Rock Reservation community ran completely out of water during drought.

Agriculture, particularly livestock ranching, is a principle economic livelihood for many tribal communities within the Northern Great Plains. Warmer temperatures and changes to water cycles (for example, reduced snowpack, earlier transition from snow to rain, and reduced or early runoff) pose a threat to these livelihoods. Drying and degradation of rangelands and pastures leads to soil compaction, reduced nutrients for healthy grasslands, and overall forage production, increasing livestock stress. Reduced water availability for irrigation systems throughout the region is further compounded by an outdated and crumbling infrastructure due to lack of federal funding. (For more information, see Table 22.4: Reservation Irrigation Projects: Deferred Maintenance and Replacement Costs in the Fourth National Climate Assessment.)

Tribal nations have unique water rights and layers of relevant state and federal laws, including, for example, the Winters Doctrine and state water rights adjudication, and Prior Appropriation laws in the West. Climate change impacts on water resources are likely to compound these legal complexities, especially in cases where state water laws supersede tribal water codes and water rights during times of scarcity.

Indigenous people in the region are also very concerned about the consequences of major oil pipelines passing through the region. Tribal communities are particularly concerned about potential oil leaks, which would further reduce water quality and quantity, compounding the existing impacts of water insecurities due to climate change. This concern is justified given that climate change is projected to damage infrastructure in the region, including pipelines, through extreme storms and precipitation events that have led to extensive flooding leading to property damage within the region.

2) Impacts to culture

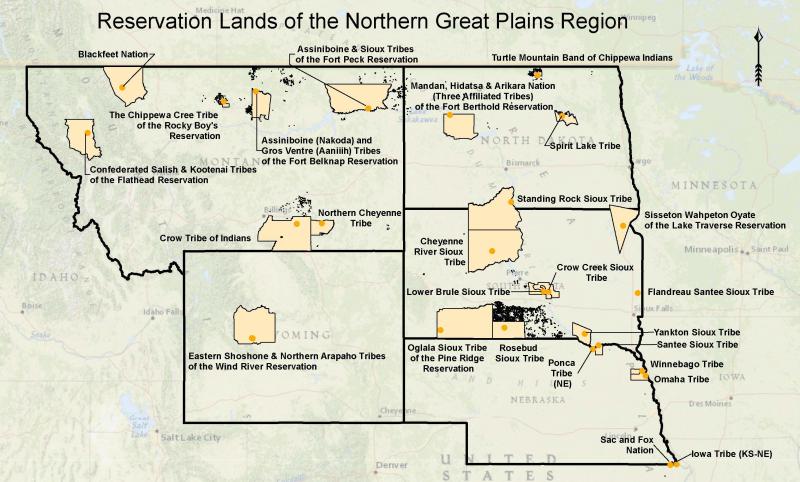

The rich cultural heritage of the Indigenous peoples of the Northern Great Plains include 28 federally recognized tribal communities (the Little Shell Band of Chippewa Indians received federal status in 2019, but still remain without land) and several federally unrecognized tribal communities and individual Native Americans living throughout towns, cities, and rural areas of the region.

Disaster management planning is extremely important for all tribal communities within the Northern Great Plains. Over the last two decades, tribal communities have experienced catastrophic fires, floods, and droughts, straining limited budgets and response capacities. Climate change is expected to increase the need for emergency management responses, particularly relative to wildfires, floods, and droughts.

Severe droughts in this century have resulted in serious economic impacts for tribal ranchers—some of whom have been forced to liquidate cattle herds—with some reservations having no access to water. Extreme hydrological events on regional reservations are happening in quick succession, such as in 2011, when floods were followed by severe drought and fire in 2012.

Each of these catastrophic extreme weather events strains response capacity, as many tribal communities struggle due to a lack of disaster preparedness, and successive events compound these challenges. Widespread climate change has negatively impacted tribal economies and livelihoods, reduced domestic and municipal water supplies, and increased health disparities within these communities.

3) Proactive adaptation and strategic planning

Native nations throughout the Northern Great Plains are addressing climate change at various time scales and utilize numerous adaptation strategies. Some nations, like the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and Blackfeet, are addressing climate change comprehensively by coordinating across all tribal departments with support from their Tribal Councils. Some tribal nations have focused on sector-specific plans to address climate change, such as the Rosebud Sioux Tribes’ Drought Adaptation Plan or the Sac and Fox of Missouri in Kansas and Nebraska’s Emergency Management Plan. Non-profit organizations have also played a role in assisting tribal communities implement on-the-ground natural resource adaptation strategies, such as Trees, Water & People providing reforestation project funding and facilitation on post-burn scar sites led by local Indigenous leaders within the Oglala Sioux Tribe on the Pine Ridge Reservation.

Tribal nations within the region are proactive in their monitoring efforts to address short-term (3–6 months) climatic impacts. Several nations across the region, including the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho, Rosebud Sioux, Flandreau Santee Sioux, and Oglala Sioux, have partnered with the High Plains Regional Climate Center to develop climate dashboards for monitoring climatic conditions on tribal lands. Climate summaries, like those developed at Sac and Fox Tribe of Missouri in Kansas and Nebraska, have served as an effective tool in monitoring microclimate changes and communicating time-sensitive information to tribal leaders and community members.

4) Collaboration and coordination

Many climate adaptation strategies have been implemented within the Northern Great Plains Indigenous communities. However, tribal nations are faced with unique legal and regulatory barriers due to post-colonial resettlement within the exterior boundaries of reservations, resulting in trust land fragmentation and inequalities of land ownership classes from land regulation by federal agencies. For example, the trust relationship with the federal government, where it holds the titles of tribal lands “in trust” for the tribal communities, requires federal permission for many aspects of land and resource management.

Tribal sovereignty is extremely important because without control and decision making over resources, adaptation is highly constrained. This has led to numerous protests by native nations to building oil pipelines and other forced and unwanted extractive development crossing within and adjacent to tribal lands that create catastrophic impacts on tribal natural resources (e.g., Standing Rock). Even changes to housing and the built environment require working with federal agencies and are subject to federal regulations, further emphasizing the importance of collaboration and coordination between federal and tribal government agencies.

Multiple tribal initiatives focus on climate and Indigenous knowledge-based education, outreach, and information sharing between tribal communities:

- The Northern Cheyenne indigenous land-based science learning program offers apprenticeships for youth interested in biocultural restoration science. The program, which sits in the tribe’s Department of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources, aims to increase tribal knowledge around Indigenous and western sciences and thus enable youth to reclaim their responsibility to the land.

- The Blackfeet and Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes collaborated on a regional workshop with First Nations throughout the region to share ideas and strategies and provide support for tribal climate adaptation planning.

Tribal communities are increasingly drawing on their deep, place-based connections to natural cycles and Indigenous knowledge, combined with western technical sciences, to respond to and prepare for climate change.

The preceding text is excerpted and abridged from the report Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II (Chapter 22, Northern Great Plains).

5) Points of contact

Federal agencies, through regional groups, are working with tribal communities to address climate-related threats and opportunities and building climate resilience in the Northern Great Plains region.

5.1) Northern Great Plains Tribal Climate Service Providers

- Bureau of Indian Affairs Tribal Climate Resilience Program

- Stefan Tangen—Tribal Resilience Liaison: stefan.g.tangen@gmail.com and/or stefan.tangen@colorado.edu

- Alyssa Samoy —Tribal Resilience Staff: alyssa.samoy@bia.gov

- North Central Climate Adaptation Science Center Help Desk

- North Central Climate Adaptation Science Center: Tribal Climate Adaptation YouTube Webinars

- North Central Climate Adaptation Science Center: Tribal Climate Monthly Newsletters

To learn more about climate impacts and adaptation in tribal communities, visit the Tribal Nations topic.

- 1Yellowtail, Thomas, and Michael Oren Fitzgerald. Native Spirit: The Sun Dance Way. Bloomington, IN: World Wisdom, 2007.