Forestry

Forests are a defining characteristic of Midwest landscapes, covering more than 91 million acres. Forest ecosystems sustain the people and communities within the region by providing ecological, economic, and cultural benefits. The economic output of the Midwest forestry sector totals around $122 billion per year; forest-related recreation adds to the region’s economy. Forests are also fundamental to cultural and spiritual practices of tribal communities, supporting plants and animals of cultural importance and providing food and resources for making items such as baskets, canoes, and shelters.

Climate change is anticipated to have a pervasive influence on Midwest forests over the coming decades. Longer growing seasons and increased carbon dioxide concentrations have benefited tree growth rates and forest productivity, but these benefits will continue only if adequate moisture and nutrients are available to support the higher growth rates.

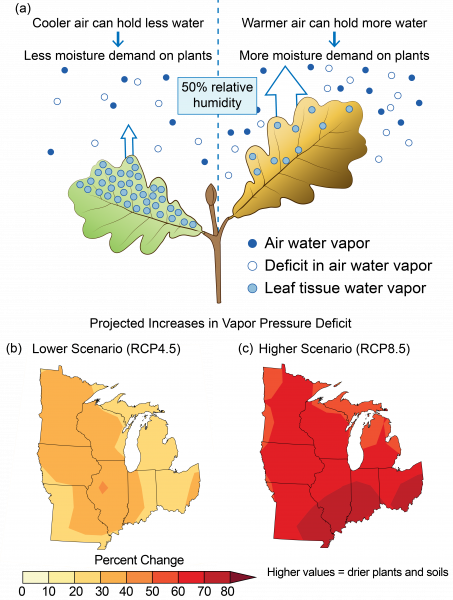

Rising growing-season temperatures will increase the frequency of drought stress from drier soils and air (see the figure), and will likely result in reduced tree growth and widespread tree mortality.

An increase in the mortality of younger trees, which are particularly sensitive to drought, may result in a shift in the composition and structure of Midwest forests. Warming winters will reduce snowpack that acts to insulate soil from freezing temperatures, increasing frost damage to shallow tree roots and reducing tree regeneration. The negative effects of insect pests and tree pathogens are anticipated to intensify as winters warm, increasing winter survival of pests and allowing them to expand into new regions. Overall, the increasing stress on trees from rising temperatures, drought, and frost damage raises the susceptibility of individual trees to the negative impacts from invasive plants, insect pests, and disease agents.

Impacts from human activities such as logging, fire suppression, and agricultural expansion have lowered the diversity of the Midwest’s forests. Reduced diversity results in an increased risk to the negative effects of climate change, given the reduction in the number of tree species and age classes that are resistant to biological stressors. Forests with lower tree diversity are more susceptible to widespread mortality and declines in productivity. Changes in climate and other stressors will likely result in changes in forest types and composition as tree species at the northern limits of their ranges decline and southern species experience increasingly suitable habitat. However, the fragmentation of the forests and the flatness of the terrain may limit the ability of particular species to shift to future suitable habitats. With projected shifts in forest composition in the central hardwood region (southern Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio) by the end of the century under a higher emissions scenario, substantial declines in wildlife habitat and the economic value of timber (a projected decline of up to $788 billion in 2015 dollars) may be expected by the end of the century.

Changing climate conditions cause both cultural and economic impacts in the Midwest, and it’s very likely these impacts will worsen in the future. Many tree species on which tribes depend for their culture and livelihoods—paper birch, northern white cedar, and quaking aspen, for example—are highly vulnerable to temperature increases. Mortality of black ash trees, which are important for traditional basket-making for many tribes, is likely as winter temperatures continue to rise. Populations of the emerald ash borer, a destructive invasive insect pest that attacks native ash trees, will increase due to warming winters in the region.

Warming winters already have economic impacts on the forest industry. The timing of suitable conditions for forestry operations has become shorter and more variable. In the upper Midwest, the duration of frozen ground conditions suitable for winter harvest has been shortened by 2 to 3 weeks in the past 70 years, and the contraction of winter snow cover and frozen ground conditions has increased seasonal restrictions on forest operations in these areas. The economic impacts to both the forestry industry and woodland landowners manifests through reduced timber values.

Adaptation

Regional forestry professionals are increasingly considering the risks to forests from climate change and are incorporating climate adaptation into land management.

For example, more than 150 organizations have participated in the Climate Change Response Framework, an approach to climate change adaptation led by the U.S. Forest Service. This framework focuses on activities that enhance species and structural diversity of existing forest communities and on management approaches that aim to increase the prevalence of species that are better suited to future climatic conditions.

Forest management on tribal lands and ceded territory integrates Scientific Ecological Knowledge of natural resource management with Traditional Ecological Knowledge, a localized, place-based system of knowledge learned and observed over many generations. This integration can inform the co-creation of approaches to climate adaptation, important for maintaining healthy, functioning forests that continue to provide cultural and spiritual benefits. To learn more about TEK, visit the Tribal Nations section of this site.

The preceding text is excerpted and abridged from the report Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II (Chapter 21, Midwest).

To learn more about climate impacts to forests, visit the Ecosystems topic.