Agriculture

Key Points:

- Agriculture is an integral component of the economy, history, and culture of the Northern Great Plains.

- Rising temperatures and changes in extreme weather events are having negative impacts on some agricultural systems in parts of the region.

- A longer frost-free period could benefit agriculture in some ways; for example, by extending the grazing season or enabling new crop varieties. However, it could also increase pests, weeds, and invasive species.

- Changing precipitation patterns, together with higher temperatures, are intensifying wildfires, which can reduce forage in rangelands and forests.

- Creating a plan to manage climate risk and enhance the adaptive capacity of an agricultural operation is a four-step process that involves answering questions about the operation’s vulnerability to extreme weather and the changing climate.

- Adaptation to increasingly extreme weather and climate change might require transformative changes in agricultural management, such as regional shifts of agricultural practices and enterprises.

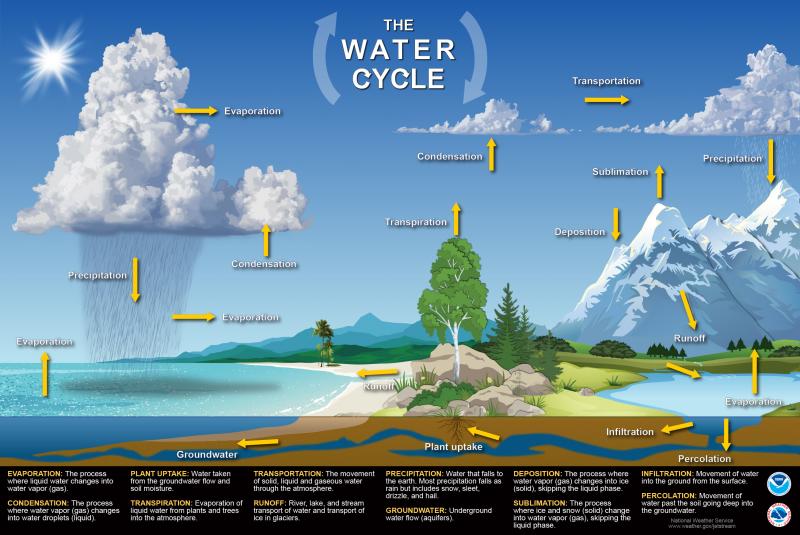

Since the mid-1800s, nearly one-half of the Northern Plains mixed-grass prairie1 and one-third of the broader Great Plains grassland areas2 have been converted to croplands through extensive tillage, including 60–70 percent of grasslands in the eastern Great Plains and <30 percent in the western Great Plains.3 These major land-use conversions changed the water cycle and the movement of carbon, nitrogen, and other nutrients through the land, water, and air.

The water cycle was also greatly disrupted by the near elimination of the region’s beaver, which were keystone species.4 Removal of beaver dams altered the water cycle, reducing the amount of water stored in soil and increasing total runoff. Interest is growing, however, in beaver reintroduction and beaver dam analogs to help restore water infiltration and natural storage capacity within watersheds. Cropland owners and managers are also increasingly interested in the five principles of soil health (see Box 1) to combat soil compaction, erosion, and loss of organic matter, which have reduced water infiltration and increased runoff.

Today, agriculture takes many forms in the Northern Great Plains, from irrigated crops to dryland farming (also known as rainfed farming), as well as forestry and the nation’s largest contiguous swath of rangelands, which support diverse wildlife species and domestic livestock grazing. These land uses represent nearly one-quarter of our nation’s farmland and permeate the economy and culture of the Northern Great Plains region.5 The region produces beef, dairy, sheep, hogs, and other livestock. Major crops include corn, soybeans, wheat, alfalfa, and hay; other crops include potatoes, sugar beets, dry beans, sunflowers, millet, canola, and barley. Minor crops, fruits, and agroforestry are intermixed, with a smaller footprint on the landscape.

Box 1: Five Principles for Restoring and Maintaining Soil Health

- Providing Soil Armor (plant and animal residue on the soil surface)

- Minimizing Soil Disturbance

- Increasing Plant Diversity

- Ensuring Continual Live Plant and Root Biomass

- Integrating Livestock

Learn more at Soil Health: Principle 1 of 5–Soil Armor | NRCS North Dakota (usda.gov).

USDA NRCS provides both technical and financial assistance to agricultural producers on a voluntary basis to help implement soil health and water-cycle restoration practices.

USDA FSA and RMA, as well as Conservation Districts, Extension, and others, provide assistance to agricultural producers for conservation and risk management practices.

Climate change impacts

Climate change is creating new challenges and opportunities for agricultural land managers. A longer frost-free season might extend the grazing season or enable crop varieties that require more growing degree days,6 but it can also increase pests, weeds, and invasive species. Also, the risk of frost striking late in the spring or early in the fall still exists, when earlier-planted crops might be in more vulnerable growth stages. The possible benefits of longer frost-free periods are also limited in part by longer dry spells, which are causing more soil moisture deficits. According to Edwards et al. (2019), climate change is bringing warmer temperatures in all seasons, resulting in more water stress and shifts in native plant communities.7 Hot days and nights are getting hotter, and warmer late-year temperatures are all bringing challenges, including changing growing conditions for crops and more wildfire risk in the case of forests and rangelands, as described below.

Drought and Wildfire. In 2017 and 2020, large portions of the Northern Plains felt the effects of severe drought, with major economic losses for agricultural producers, land managers, and rural economies.8 Forage and hay production were below average, resulting in higher feed prices. Many livestock producers reduced their herd size to avoid overgrazing and protect the ability of drought-stressed rangelands to recover. Drought conditions also resulted in historically large wildfires, which not only further reduced forage availability for livestock, but also altered critical wildlife habitat, closed recreational areas, reduced air quality for downwind communities, and impacted water quality from forested watersheds. Fire danger was especially high in forested areas with large diebacks from mountain pine beetle. Climate change is contributing to longer and more intense wildfire seasons in Northern Plains forests and rangelands by causing spring green-up to arrive earlier, dry spells to last longer, hot days and nights to be hotter, and warm conditions to occur later in the year.

Compounding Extremes. An increase in back-to-back extreme events could result in cascading or compounding effects to agriculture. Recent events serve as important guideposts. In 2019, one of the costliest inland floods in U.S. recorded history swept through the Missouri River Basin, affecting portions of Nebraska, South Dakota, and North Dakota. The flooding resulted in an estimated $10 billion in damages, including the loss of roads, bridges, railways, levees and dams; degradation of agricultural lands, buildings, and equipment; and the stranding of thousands of cattle.9 This historic flood was caused by a sequence of extreme weather events,10 beginning in the fall of 2018, when above-normal precipitation filled the soil profile. Soils then froze deeply in late winter, due to heavy snowfall and below-normal winter temperatures, which caused thick ice to form on rivers and streams. In March of 2019, a record-breaking spring storm caused an extreme rain-on-snow event, which generated excessive runoff that quickly overwhelmed ice-jammed waterways. As climate in the Northern Plains continues to change, the weather is expected to become more variable, possibly resulting in more back-to-back extreme events, resulting in cascading or compounding effects,11 as seen in 2019.

Assessing vulnerability and risk

Vulnerability is a key concept in understanding an agricultural operation’s climate risk. Thinking about climate risk in terms of sensitivity (the response of individual components of the production system to exposures) and adaptive capacity (the ability of the production system as a whole to buffer damages and capture new opportunities) can help assess an agricultural operation’s vulnerability. In turn, this allows land managers to develop both short- and long-term strategies that are more likely to sustain an agricultural operation as weather patterns become more variable and extreme.

Creating a plan to manage climate risk and enhance the resilience of an operation is a stepwise process that involves answering four questions about the vulnerability of an operation to changing weather conditions:

- What are the key weather-related challenges for your operation?

- What are the key production threats from changing weather patterns and extremes?

- What are your options for addressing key weather-related threats?

- What is the best mix of adaptation options?

For more information, see “Cultivating Climate Resilience on Farms and Ranches.”

Adaptation

Adaptation to extremes and to longer-term climate change might involve transformative changes in agricultural management, including regional shifts of agricultural practices and enterprises. Restoring the cycling of nutrients and water in agricultural watersheds—for example, through soil health practices (see Box 2) and beaver analogs or reintroduction—is critical to addressing climate-related changes and challenges.12

Agricultural producers already have several management practices in their toolbox for increasing resilience to extreme weather and a changing climate, such as diversifying crop rotations, reducing tillage, incorporating cover crops, improving irrigation efficiency (not just at the field level, but also at the watershed or aquifer level), returning marginal croplands to permanent cover, using flexible stocking strategies and adaptive grazing management, improving water infrastructure in pastures and rangelands, and enrolling in financial instruments or assistance programs that can help mitigate otherwise unavoidable weather risks (e.g., USDA’s Rainfall Index - Pasture, Range & Forage insurance program).

Box 2: Healthy Soils

Healthy soils give us clean air and water, bountiful crops and forests, productive grazing lands, diverse wildlife, and enjoyable landscapes. Soils do this by performing five essential functions:

- Regulating water. Soil helps control where rain, snowmelt, and irrigation water goes. Water and dissolved solutes flow over the land, or into and through the soil.

- Sustaining plant and animal life. The diversity and productivity of living things depend in part on soil.

- Filtering and buffering potential pollutants. The minerals and microbes in soil are responsible for filtering, buffering, degrading, immobilizing, and detoxifying organic and inorganic materials, including industrial and municipal by-products and atmospheric deposits.

- Cycling nutrients. Carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and many other nutrients are stored, transformed, and cycled in the soil.

- Physical stability and support. Soil structure provides a medium for plant roots. Soils also provide support for human structures and protection for archeological treasures.

See Healthy Soil for Life for more details.

As climate change poses new challenges for agriculture in the Northern Plains, building and protecting soil health and productivity are important. By using soil health principles and region-appropriate practices, such as no-till, diverse rotations, cover crops where feasible, and the 4 R’s of nutrient management, more and more farmers are increasing soil organic matter. As a result, they are sequestering more carbon, increasing water infiltration, improving wildlife and pollinator habitat—all while harvesting better profits in many cases. See Soil Health | NRCS (usda.gov) for more information.

Adaptation resources and assistance

Several U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) agencies administer programs that provide technical and financial assistance for reducing the many sources of risk that agriculture and forestry face, including those related to weather and climate. These programs—examples are provided in the table below—play a vital role in supporting working lands management in an increasingly variable climate. They assist with preparedness, response, and recovery, including assistance with weather-ready or climate-smart practices such as reduced-tillage, diverse crop rotations, cover crops, nutrient management, and restoration of forested working lands and other permanent vegetation such as perennial grasses, buffer strips, shelterbelts, and other forms of agroforestry. Two USDA agencies—NRCS and FSA—are often co-located in county-level offices throughout the country, known as USDA Service Centers. These agency staff are well-positioned to provide support before, during, and after extreme weather events and climate-change risks.

Complementing these agencies’ efforts are the outreach and convening efforts of the USDA Climate Hubs. This network of 10 Climate Hubs, located across the U.S., provides climate-related information, tools, and partnerships tailored for agriculture and forestry within each unique region. The Hubs excel at making climate science more accessible to working land managers and their trusted technology-transfer partners. They also specialize in convening these groups to discuss weather and climate-related challenges, then conveying needs back to researchers and policymakers in order to strengthen the relevance and usefulness of their efforts in the future.

Private industry is also creating partnerships and incentive programs for agricultural producers to meet growing consumer demand for more “sustainable” or “regenerative” food and fiber products. One partnership among a well-known NGO, food processor, and food retailer is restoring 8,000 acres of cropland to grassland for grazing beef cattle. Other large corporations are funding projects to grow food and fiber in more sustainable or regenerative ways as part of their strategy to sell high-value products that consumers associate with positive environmental outcomes.

| Program | USDA Agency | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) | Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) | Assists agricultural producers with planning an implementation of conservation practices that can lead to water conservation and recharge, cleaner water and air, healthier soils, and better wildlife habitat, all while improving agricultural operations. |

| Emergency Watershed Protection Program (EWPP) | NRCS | Helps communities address hazardous watershed impairments, including re-seeding drought-stricken areas prone to erosion that could pose a threat to life or property. |

| Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) | NRCS | Helps build conservation efforts while strengthening operations through activities such as scheduling timely planting of cover crops, developing a grazing plan that will improve the forage base, implementing no-till to reduce soil erosion and increase water infiltration, or managing forested areas in ways that benefit wildlife habitat. |

| Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP) | NRCS | Encourages partners to join efforts with producers to increase restoration and sustainable use of soil, water, wildlife, and related natural resources on regional or watershed scales. |

| Emergency Conservation Program | Farm Service Agency (FSA) | Provides emergency funding for farmers and ranchers to rehabilitate land severely damaged by a natural disaster or to implement emergency water conservation measures during severe drought. |

| Emergency Farm Loan Program | FSA | Offers low-interest emergency loans to qualifying producers in eligible counties to restore or replace essential property, pay production costs incurred during the affected year, pay essential family living expenses, or refinance certain debts. |

| Livestock Forage Disaster Program (LFP) | FSA | Compensates eligible livestock owners for grazing losses on eligible pastures due to drought, and producers who lose access to federal grazing allotments due to wildfire. |

| Livestock Indemnity Program (LIP) | FSA | Compensates eligible livestock owners and contract growers for excess livestock deaths due to an eligible disaster. |

| Emergency Livestock Assistance Program (ELAP) | FSA | Compensates any remaining feed or water shortages not adequately addressed by LIP or LFP, including the cost of hauling water to eligible affected livestock. |

| Tree Assistance Program (TAP) | FSA | Provides assistance to eligible orchardists and nursery tree growers for qualifying tree, shrub, and vine losses due to drought. |

| Disaster Set-Aside Program (DSA) | FSA | Allows FSA borrowers in disaster-designated areas to postpone one FSA loan installment until the loan’s final due date. |

| Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program (NAP) | FSA | Provides financial assistance to producers of non-insurable crops to protect against natural disasters that result in lower yields or crop losses, or prevent crop planting. |

| Agricultural Risk Coverage (ARC) | FSA | Provides revenue loss coverage at the county level. Payments are issued when the actual county crop revenue of a covered commodity is less than the ARC-CO guarantee for the covered commodity. |

| Multi-Peril Crop Insurance (MPCI) | Designed by Risk Management Agency (RMA); sold by private crop insurance companies | Covers individual crops against eligible weather-related yield losses. |

| Whole Farm Revenue Protection (WFRP) | RMA; private insurance companies | Covers multiple crops and/or livestock under the same policy (making it especially useful for highly diversified farms and ranches). It simultaneously covers yield losses and/or price-related losses. |

| Rainfall Index—Pasture, Range & Forage (RI-PRF) Insurance | RMA; private insurance companies | Covers precipitation shortfalls in pasture, rangeland, or forage areas. Based on precipitation data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). |

| Livestock Gross Margin (LGM) | Private insurance companies | Covers market value of livestock minus feed costs. |

| Crop-Hail Insurance | Private insurance companies | Covers losses due to hail. Additional coverage may cover crop damage from fire, lightning, transit after harvest to storage, vandalism, replanting costs, and reduction in expected yield due to the later planting date. Policies available for major grain and hay crops, but more limited for specialty and vegetable crops. |

Box 3: Learn More

- Resilient Agriculture: Weather Ready Farms eFieldbook

- This eFiieldbook provides information for outreach professionals and agricultural producers interested in learning about weather and climate-related challenges in agriculture and ways to build resiliency.

- It was developed by Extension at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Purdue University, the USDA Climate Hubs, and the High Plains Regional Climate Center.

- Read more about this e-publication here.

- Scenario Planning for Crops and Cattle

- Collaborative Adaptive Rangeland Management (CARM) Project website

- CARM eletronic fact sheet: Beef & Birds: Can conservation and beef production find common ground?

- Learning from Your Neighbor: Climate Resiliency in Agriculture is a StoryMap with stories from six agricultural producers in the region who are using one or more of these climate-smart practices:

- Minimum tillage or no-till

- Crop rotation

- Mixed crop and livestock grazing systems

- Note: This is a living project, and more stories and content could be added.

- No-Till Resources

- USDA Northern Plains Climate Hub’s No-Till: From Science to Action webpage

To learn more about climate impacts and adaptation in the agricultural sector, visit the Food topic.

- 1Comer, P.J., J.C. Hak, K. Kindscher, E. Muldavin, and J. Singhurst, 2018. "Continent-Scale Landscape Conservation Design for Temperate Grasslands of the Great Plains and Chihuahuan Desert." Natural Areas Journal 38(2), 196–211.

- 2Cunfer, G., 2005. On the Great Plains: Agriculture and Environment. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN-10:1585444014

- 3Hartman, M.D., E.R. Merchant, W.J. Parton, M.P. Gutmann, S.M. Lutz, and S.A. Williams, 2011. "Impact of historical land‐use changes on greenhouse gas exchange in the U.S. Great Plains, 1883–2003." Ecological Applications 21(4), 1105–1119.

- 4Naiman, R.J., C.A. Johnston, and J.C. Kelley, 1988. "Alteration of North America streams by beaver." BioScience 38(11), 753-762.

- 5USDA, 2018: Census of Agriculture. 2012 Census Volume 1, Chapter 2: State Level Data. U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service, Washington, DC.

- 6Hibbard, K.A., F.M. Hoffman, D. Huntzinger, T.O. West, and B.C. Stewart, 2017. "Changes in Land Cover and Terrestrial Biogeochemistry." In D.J. Wuebbles, D.W. Fahey, K.A. Hibbard, D.J. Dokken, and T.K. Maycock (Eds.), Climate Science Special Report: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume I (pp. 277-302). US Global Change Research Program.

- 7Edwards, B.L., N.P. Webb, D.P. Brown, E. Elias, D.E. Peck, F.B. Pierson, C.J. Williams, and J.E. Herrick, 2019. "Climate change impacts on wind and water erosion on US rangelands." Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 74(4), 405-418.

- 8a8bJencso, K., B. Parker, M. Downey, T. Hadwen, A. Howell, J. Rattling Leaf, L. Edwards, A. Akyuz, D. Kluck, D. Peck, M. Rath, M. Syner, N. Umphlett, H. Wilmer, V. Barnes, D. Clabo, B. Fuchs, M. He, S. Johnson, J. Kimball, D. Longknife, D. Martin, N. Nickerson, J. Sage, and T. Fransen, 2019. Flash Drought: Lessons Learned from the 2017 Drought Across the U.S. Northern Plains and Canadian Prairies. NOAA National Integrated Drought Information System.

- 9NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Events (2019). Missouri River and North Central Flooding, March 2019.

- 10Nebraska State Climate Office, 2019. "Flood Stands Out in History." In Climate Crossroads: Quarterly Newsletter, Summer 2019 (pp. 3-4). University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

- 11Kopp, R.E., K. Hayhoe, D.R. Easterling, T. Hall, R. Horton, K.E. Kunkel, and A.N. LeGrande, 2017. "Potential surprises: Compound Extremes and Tipping Elements." In: D.J. Wuebbles, D.W. Fahey, K.A. Hibbard, D.J. Dokken, and T.K. Maycock (Eds.), Climate Science Special Report: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume I (pp. 411-429). U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA.

- 12Lal, R., J.A. Delgado, P.M. Groffman, N. Millar, C. Dell, and A. Rotz, 2011. "Management to mitigate and adapt to climate change." Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 66(4), 276-285.