Water

Key Points:

- Effective water management is essential for people, crops and livestock, ecosystems, and the energy industry.

- Small changes in annual precipitation have large effects downstream.

- Increased climate variability may result in more extreme events.

- Projections include future changes in precipitation patterns, warmer temperatures, and the potential for more extreme rainfall events.

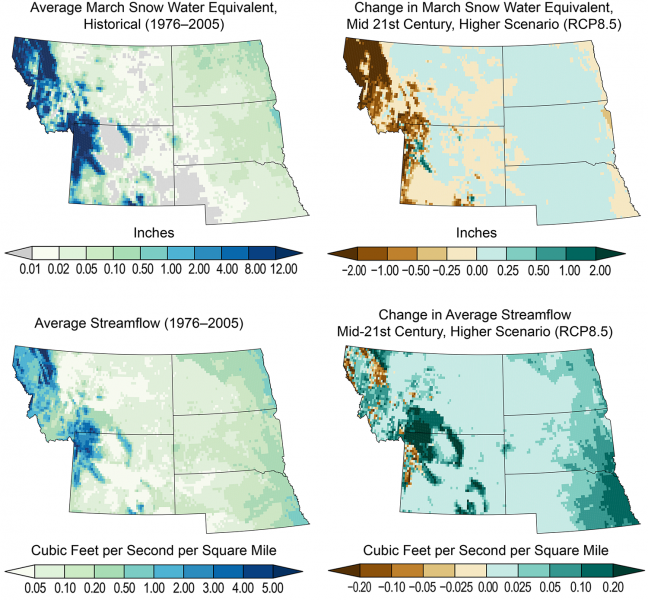

Climate drives extreme fluctuations throughout the five states of the Northern Great Plains. In some cases, evaporation rates exceed 100 percent of precipitation, resulting in a deficit of surface water and more reliance upon groundwater. Cool season moisture—from snowfall and snowpack—is essential for groundwater and aquifer recharge, and those rates are relatively high in the region.

Water management is intricately tied to both flooding and drought throughout the region. Indications point to a shift in peak seasonal runoff for the Upper Missouri Basin based on climate modeling results.1 Shifting peak runoff will cause disruption with energy production, ecosystems, and reservoir and water management. In addition, increased variability in upper Missouri River runoff (above Sioux City) will continue to be a major concern for interests along the river corridor.2

Flooding

Runoff has become much more volatile since 1970, as dry spates followed by extreme precipitation events have become more common. Major flooding across the Upper Missouri River Basin in 2011, 2018, and 2019 figure prominently in recent memory. Both 2018 and 20193 were record-setting years for precipitation and flooding.4 Flooding began in March 2019 in Nebraska, Iowa, Missouri, and South Dakota and remained relentless throughout the year, setting many precipitation and flood records.

Drought

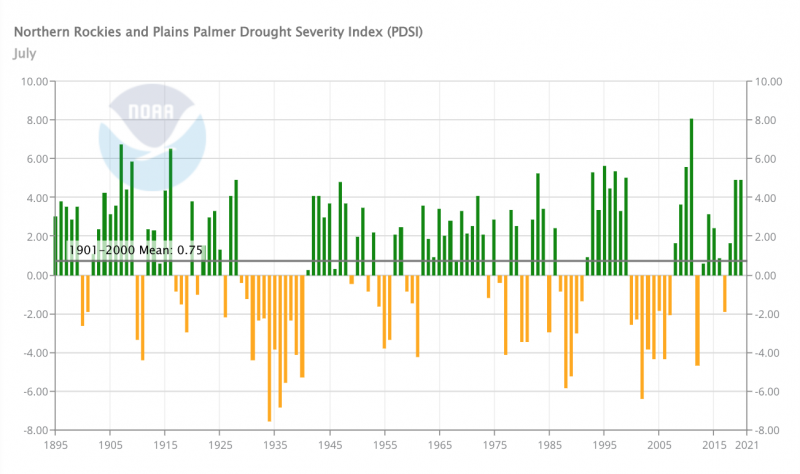

Prolonged regional droughts in the 1930s and 1950s substantially affected water supplies, agriculture, energy, transportation of goods, and ecosystems. More recent, short-duration droughts have also impacted the Missouri River basin.

There has been a dearth of monitoring for precipitation, soil moisture, and snow water equivalent (a measure of water stored seasonally in snowpack) at low elevations, leading the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) to establish an Upper Missouri River Basin Soil Moisture and Plains Snow and Soil Moisture Monitoring Network (UMRB Monitoring Network). Coverage includes Montana, Wyoming, the Dakotas, and northern Nebraska. The USACE is collaborating with federal and state partners to implement this project following recommendations made in 2013 after a very wet 2011 and a very dry 2012.

When it comes to weather-related events, having the most accurate, up-to-date information is one of the best tools we have to help mitigate potentially devastating consequences.

—John Thune (R-S.D.)5

The rapid evolution of drought in 2012 underscored the need to anticipate drought. In 2017, record low May–July precipitation, warm temperatures, and windy conditions led to rapid soil moisture declines in the upper basin. Neither the drought’s swift onset nor its severity were forecasted. By July 2017, North Dakota, South Dakota, eastern Montana, and the Canadian prairies were experiencing severe to extreme drought, wildfires spanning some 4.8 million acres, livestock losses, and agricultural losses of more than $2.6 million in the U.S. alone.

Building resilience

Critical Tools and Reports

- NOAA's Monthly Midwest and Northern Plains Regional Climate Summary and Outlook Series

- High Plains Regional Climate Center Climate Summaries

- Flash Drought: Lessons Learned From the 2017 Drought Across the U.S. Northern Plains and Canadian Prairies

- The Causes, Predictability, and Historical Context of the 2017 U.S. Northern Great Plains Drought

- Upper Missouri River Basin Drought Indicators Dashboard

Reservoir management

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers manages the Missouri River through the Master Manual, a 432-page document that lays out eight congressionally authorized purposes: flood control, river navigation, hydroelectric power, irrigation, water supply, water quality, recreation, and fish and wildlife (including preservation of endangered species). The Missouri River Mainstem Reservoir System was designed to support these eight authorized purposes through long, extended droughts.

The 1930–1941 12-year Depression-era drought is the "design drought" used to determine how much "conservation" storage is needed for a long, extended drought. As outlined in Chapter 7 of the Master Manual, water conservation measures are implemented as a drought worsens. For example, during the last extended drought (2000–2007), water conservation measures were implemented (e.g., less-than-full navigation flow support, shortened navigation season, reduced winter releases) in July 2000. Once the drought was over in 2007, it took nearly two more years of water conservation measures for the system to fully recover from the drought.

Drought Early Warning

The National Integrated Drought Information System (NIDIS) developed a Drought Early Warning System (DEWS) for the Missouri River Basin in 2014. The goal is to improve the regional capacity to respond to and cope with drought by utilizing existing networks of federal, tribal, state, local, and academic partners to make climate and drought information readily available and useful for decision makers.

The floods of 2019 were followed by widespread drought in the latter half of 2020. In December 2020, NIDIS and partners released the Missouri River Basin DEWS Strategic Action Plan, which outlines priority tasks and activities to build drought early warning capacity and resilience. This plan is the second iteration for this region, and builds upon the first plan to include a new focus on enhancing tribal capacity to use drought information and new tools, including drought indicators, across the region (for more information, visit the Northern Great Plains | Indigenous Peoples and the Tribal Nations | Capacity Building pages of this website and the Tribal Engagement page from the U.S. Drought Portal). It considers the needs and gaps that were exposed during the 2017 Northern Plains flash drought, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers efforts to strengthen soil moisture monitoring in the region, as well as efforts to better understand the needs of tribal nations in the basin.

To learn more about climate-related impacts on water, visit the Water topic.

- 1Stamm, J.F., Dennis Todey, Barbara Mayes Boustead, Shawn Rossi, P.A. Norton, and J.M. Carter, 2016. Modern (1992–2011) and projected (2012–99) peak snowpack and May–July runoff for the Fort Peck Lake and Lake Sakakawea watersheds in the Upper Missouri River Basin (ver. 1.2, June 2016). U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2015–5135, 44 p., dx.doi.org/10.3133/sir20155135.

- 2NOAA and CIRES, 2016. Explaining Hydrological Extremes in the Upper Missouri River Basin (PDF).

- 3Flanagan, Paul Xavier, Rezaul Mahmood, Natalie A. Umphlett, Erin Haacker, C. Ray, William Sorensen, Martha Shulski, Crystal J. Stiles, David Pearson, and Paul Fajman. "A Hydrometeorological Assessment of the Historic 2019 Flood of Nebraska, Iowa, and South Dakota," Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 101, 6 (2020): E817-E829, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-19-0101.1

- 4Umphlett, Natalie, Doug Kluck, and Dennis Todey, 2020. Extreme Wetness of 2019(PDF).

- 5U.S. Senator Mike Rounds (September 29, 2020). "Rounds, Thune, Johnson: Army Corps Announces Major Step Toward Implementation of Snowpack Monitoring System." Press release.