Fresh out of graduate school, Chris Carparelli joined AmeriCorps and put his education to work by serving the community. Though he had few financial resources at his disposal, Carparelli used his knowledge of water management and drought planning—and worked extensively with a comprehensive set of stakeholders—to develop a drought resiliency plan for the Beaverhead Watershed of Montana.

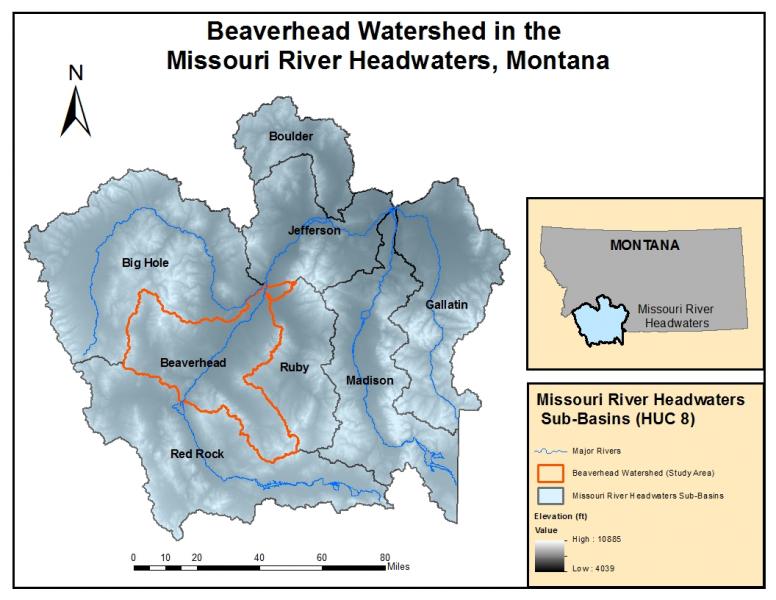

Water for the Beaverhead River and other watersheds that feed the Missouri River comes from snowmelt in the Rocky Mountains of southwest Montana. During summer 2014, Montana Governor Steve Bullock announced that the Missouri River headwaters would be the location of a pilot project for the National Drought Resilience Partnership, an initiative to build national capabilities for long-term drought resilience. In 2015, the Beaverhead Watershed Committee brought Carparelli on board to produce a drought resiliency plan.

One river, many uses

Water from the Beaverhead River supports agricultural and livestock operations across Beaverhead County. Food production is the primary economic driver in the county, which ranked first in beef production and third in sheep production among all of Montana’s counties in 2013. Across this agricultural region, weather and climate conditions can have a direct effect on the economic well-being of local communities.

The Beaverhead River’s status as a Blue Ribbon fishery for brown trout ties its local economy even more closely to climate variability: when drought causes low river flows or high air temperatures result in increased water temperature, angling recreation—and the income fishing brings to local businesses—drops significantly.

Changing conditions

Climate change is already evident in the Beaverhead Watershed. Through his interactions with stakeholders, Carparelli compiled a list of climate-related issues identified by stakeholders in the watershed:

- Earlier spring runoff

- Lower peak runoff

- Decreased streamflow in late summer

- Warmer stream temperatures

- Increased evapotranspiration promotes snowmelt, increases surface evaporation of reservoirs, and stresses crops

- Increased noxious weed pressure

- Potential for longer and more intense wildfire seasons

- Limited water availability increasing conflicts between stakeholders due to competing uses

As the Beaverhead Watershed is sparsely populated, local resources for addressing these issues are limited. However, the opportunity to participate in a pilot project for a national partnership gave local stakeholders extra motivation to effect change at the local level, and individuals and groups began working together toward increasing their resiliency to drought.

Developing the drought resiliency plan

When Carparelli arrived in Dillon, Montana, he started with a focus on the Bureau of Reclamation’s six elements for drought contingency planning. Among the elements are monitoring, vulnerability assessment, and mitigation and response actions.

One concrete step he took was identifying gaps in streamflow monitoring throughout the watershed. Carparelli also built relationships with agency personnel and stakeholders to understand which issues were the highest priorities and to assess the watershed’s vulnerability to drought. Many of his interactions were informal: he attended meetings to listen and take notes that would help him understand issues across the watershed. Meeting with individual stakeholders on their turf helped him gather more focused and unfiltered impressions about local vulnerabilities to drought. These meetings also netted many local recommendations for mitigation of the issues.

For each vulnerability identified during the information-gathering phase, Carparelli listed potential response actions in the drought plan. For example, noting the lack of streamflow monitoring on the Red Rock River—an important source of water supply for Clark Canyon Reservoir—the plan recommended installing additional stream gauges.

A ready-to-use plan

The drought resiliency plan is now complete and ready to be consulted when dry or drought conditions come around. The plan will also be incorporated as an appendix to the Beaverhead County Hazard Mitigation Plan. However, as Carparelli has moved on from his position with the Big Sky Watershed Corps, the challenge will be to keep the plan up-to-date for the future.

Carparelli says, “I don’t really know what the future holds for it [the plan]…all plans run the risk of becoming ‘shelf art.’ The plan doesn’t really matter if you don’t have people engaged in the planning process and dedicated to the process of implementing and updating the drought plan.”

In order for the plan to become a living document, Carparelli believes that local stakeholders, such as the Beaverhead County Drought Task Force, the Beaverhead Conservation District, or local irrigation districts, will need to take ownership of it, though small staffs at these entities may make this a continual challenge. And all the while, climate continues to change, introducing new challenges for effective management of natural resources across the watershed.

The first step has been taken, though: the drought plan represents a successful collaboration among local stakeholders and agencies. At some point in the future—when changing conditions incite stakeholders to consult the plan—they will have recommendations to consider, or they can build on the plan to help them adapt to new conditions.