From field to farm to forest to cities, the ecosystem we know is supported by native and introduced pollinators.

Commercial crop pollination by domesticated honey bees is essential to one-third of all food and beverages consumed in the United States, and some crops—including almonds, apples, berries, cucumbers, and squash—are almost entirely reliant on pollination. "The world's 20,000 bee species and other pollinators are critical to food security," says Phyllis Stiles, a pollinator advocate and founder of the non-profit Bee City USA®. In fact, she explains, pollinators “are responsible for reproduction of three-quarters of the world's known plant species."

Understanding how pollinator populations are affected by climate change, and how humans can act to counter those effects, can bolster both food production and ecosystem services such as clean drinking water, recreation, wildlife management, and forest products.

Pollinators in danger

America's pollinators are declining.

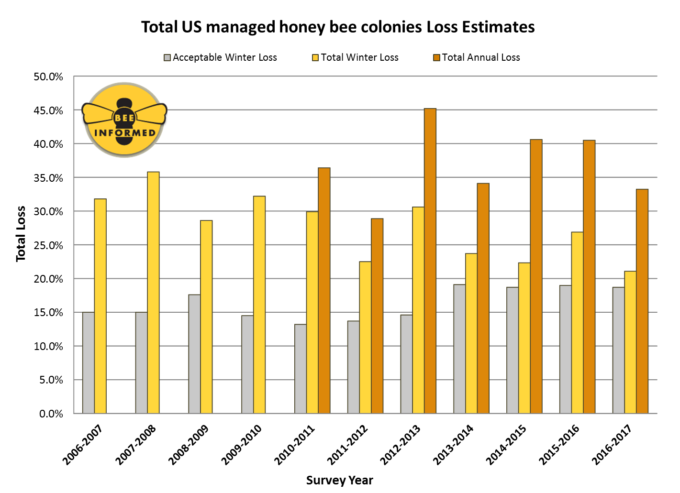

There are around 2.8 million commercial honey bee colonies in North America—down from a high of 5.9 million in 1947, but up from a low of 2.3 million in 2008. Most studies of pollinator decline have focused on domesticated honey bees used in commercial agriculture. Honey bees have multiple stressors: poor nutrition, diseases, parasites, pesticides, and “migratory stress” from being trucked from farm to farm. Researchers are coming to believe that the decline may come from a combination of all of these stressors compounding each other. While the number of colonies has held fairly steady since the mid-1990s, the annual die-off rate has increased: total annual colony loss since 2010 has ranged from 25 to 45 percent, compared to the less than 20 percent “acceptable winter loss rate” reported by beekeepers. The eastern population of monarch butterflies (important migratory pollinators that in their own right) has declined by 90 percent or more over the last two decades.

A changing climate poses additional threats to both domesticated honey bees and wild, native pollinators.

Climate effects

With a changing climate, the number and distribution of cold winter days is changing, which changes the timing and productivity of tree pollen and nectar. Data from NASA’s HoneyBeeNet show that peak nectar flow in Maryland comes almost four weeks earlier than it did in 1970. In some areas, however, warmer winters are expected to delay the bloom of flowering trees, as some tree species need low temperatures before spring warmth can trigger the end of dormancy. Both scenarios pose a problem.

Both domesticated and wild bees depend on the high flow of early bloom nectar to have a successful season. When the bloom season comes early, the bees may not yet be actively collecting nectar due to low overnight temperatures. In this case, they may miss this key foraging period. If nectar flow is late, the bees may not have enough food to sustain the colony until the bloom occurs, and they may be too weak to take advantage of the peak nectar. At this point, researchers are finding that bee activity and bloom times are keeping pace with one another in many cases. But if changes in the timing of blooms remain a trend—whether earlier or later, depending on the tree species and geographic location—there may be a point when the bloom season becomes too unpredictable for the bees to be able to successfully adapt.

Temperature increases can also put native bees at risk. Some bumble bee species had healthy populations 50 years ago but are now facing decline and, in some cases, extinction. Some evidence implicates climate change as one cause of this decline. A 2015 study found that as temperatures have risen, bumble bee habitat has shifted northward; however, some species have been unable to adapt to rising temperatures and have not migrated, resulting in shrinking distributions in the southern ends of their range.

Bee-friendly cities

Surprising new research suggests that cities may be part of the solution for restoring native pollinator populations. Urban landscapes often harbor an abundance and diversity of native bee species, even when pollinators may be absent from nearby rural lands. Some scientists believe that attending to the needs of urban pollinators—in conjunction with other conservation measures—can help the city to become a refuge for insect pollinators. Furthermore, improving cities’ wild pollinator populations may have a spillover effect to improve species richness and abundance in nearby agricultural lands, although the relative importance of cities as sources for pollinators remains unknown.

Bee City USA, a non-profit organization based in Asheville, North Carolina, is leading the charge towards cultivating more pollinator-friendly cities. Bee City USA's mission is to “enlist broad, sustained public support in creating and enhancing healthy pollinator habitat,” and the group has hosted awareness programs, promoted local nurseries, planted pollinator gardens, and encouraged greatly reduced pesticide use in Asheville.

Stiles founded Bee City USA in 2012 to galvanize organizations as varied as churches, garden clubs, breweries, and Boy Scout troops to engage in promoting the widespread biodiversity so essential to pollinator health. As of February 2018, 63 cities and 33 campuses across 32 states have been certified as Bee City USA affiliates. First and foremost, this engagement takes the form of bringing natural spaces into urban landscapes. Urban beekeeping is on the rise in cities such as Asheville, New York, Toronto, and London; the trendy hobby has helped boost awareness of the necessity of pollinators.

Stiles points out, however, that unless urban beekeepers consider honey bees’ foraging needs, they may be creating more opportunities for honey bees to rob honey from weak bee colonies and spread diseases and parasites. She says, "Just like humans, a healthy diet is key to a bee's overall immune system. All bees need a broad diversity of nectar and pollen to be able to battle the many stressors they face.”

Making your landscaping PC (pollinator-conscious)

To sustain pollinator populations, Stiles says that residential communities, institutions, businesses, and municipal departments responsible for landscaping all have the opportunity to make their landscaping "PC"—pollinator conscious. What that means is:

-

Planting native flowering plants (including trees and shrubs) that bloom in succession throughout the growing season,

-

Using pesticides only after exhausting all other options, and

-

Leaving some areas free from the harmful effects of mowing for ground-nesters.

These practices will help a variety of pollinator species and lead to a more resilient ecosystem, helping humans in return.

Taking national action to protect pollinators

Stiles isn't alone in stressing the importance of human planting practices on pollinator health. The federal government has also taken action to help preserve pollinator health and honey bee colony numbers by advising agencies and other partners on land management practices. The U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Department of the Interior jointly issued a report, Pollinator-Friendly Best Management Practices for Federal Lands, which aims to provide practical guidance for those in charge of stewarding natural resources. The initiative includes ideas such as the construction of pollinator gardens at federal buildings, and the restoration of millions of acres of federally managed lands.

Despite the difficult challenges facing America’s pollinator population, Stiles is hopeful about the positive effects federal policy and personal action will have on pollinator health. She points out, “Unlike endangered African elephants and lions, pollinators can thrive in America's urban environments. Millions of small actions, like planting flowers, can add up to monumental changes for the future of honey bees, native bees, butterflies, moths, beetles, bats, hover flies, and hummingbirds. Our goal is truly making the world safer for pollinators, one city at a time. But guess what? If we do, the world will be much safer for humans, too.”