Gambling with limited resources

For a regional conservation partnership with limited financial resources, investments in land and easements can be a big gamble.

Passionate about protecting open spaces and the habitats they support, regional conservation partnerships want to make the best investments possible to ensure long-term protection for ecosystems and wildlife. When evaluating a piece of land, they need to consider how it can contribute to meeting the needs of many species, from those with large ranges like black bear to those that rely on seasonal wetlands like spotted salamander. Adding climate change to the picture increases the complexity of investment decisions. As environmental conditions change, partnerships have to consider if a given piece of land will retain its ability to support biodiversity over time.

If not, a $20,000 parcel could come with an ecological expiration date.

A new strategy

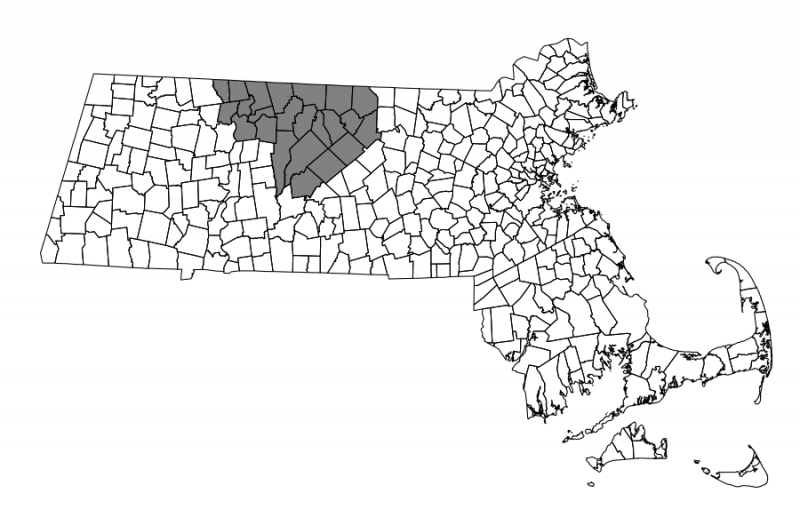

In 2013, the North Quabbin Regional Landscape Partnership—an organization encompassing a 26-town section of north-central Massachusetts—took a critical look at how they set priorities for land acquisition.

“In the past, we would put a map on the wall, use markers to circle areas where we wanted to work, and see where the zones overlapped,” recalled Matthias Nevins of the North Quabbin Regional Landscape Partnership.

In the face of increasing uncertainty, the partnership recognized the need for a more sophisticated method. They applied for and were awarded a grant from the Open Space Institute; they used the funds to help them integrate the latest climate data into a strategic, new conservation plan. The innovative new plan identifies land that can contribute to regional biodiversity, even as conditions change.

Using the new map

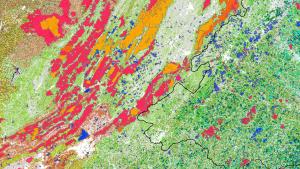

The partnership still uses a map to consider land acquisitions, but it’s no longer on the wall: “It’s a hot and cold map,” said Nevins, explaining that the web-based tool highlights places across the partnership’s region that can support rare species by protecting their habitats as well as serve as natural strongholds for wildlife as conditions change.

The map offers a strategic blueprint for climate resilience. Beyond just looking for specific habitat requirements for specific species, it incorporates information about resilient elements of the landscape itself. It also reflects geophysical features such as elevation and topography that naturally lead to ecological variety.

Additionally, the new map prioritizes areas in the landscape that will help maintain connectivity, such as properties that are adjacent to lands that are already protected. “The more connectivity, the more animals can move across the landscape as ranges shift,” explained Maggie Owens of the North Quabbin partnership.

Moving forward

The partnership is already using the map to direct strategic action in the 26-town region. When a cluster of red and orange “hotspots” on the map drew attention to an area that had not previously been considered as a high priority, the partnership decided to hold a neighborhood meeting to reach out to local landowners. “Now we are rolling out the first tax-credit land conservation program process as a result of that meeting,” explained Cynthia Henshaw, of the partnering East Quabbin Land Trust.

It’s not enough to have a map that highlights the best land to protect—truly strategic plans consider the human dimensions of conservation as well. Organizations like the Open Space Institute facilitate access to complex datasets for partnerships like the North Quabbin. In turn, the conservation partnerships make the connections with their communities. Ultimately, private land owners and town officials in the communities become stewards of resilient landscapes. Developing and providing resources like the hot and cold map helps the full range of participants visualize the importance and urgency of conservation to promote ecosystem resilience.