Salmon are integral to the ecosystem and the culture of the Pacific Northwest. In fact, salmon are considered a "keystone species" by scientists because of the benefits they provide to both aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. They also play an important role in the cultural identity of the coastal Pacific Northwest tribes. The South Fork Nooksack River in northwest Washington State is home to nine species of Pacific salmon, including spring Chinook, an iconic species for the Nooksack Indian Tribe.

In the past, the South Fork teemed with an abundance of salmon. More recently, however, their numbers have dramatically declined from historic levels, due primarily to habitat degradation. Land uses that impact water quality in the region include commercial forestry, intensive agriculture, and introduction of flood control and transportation infrastructure.

High water temperatures are detrimental to fish that depend on cool, clean, well-oxygenated water, so streams where these conditions occur are included on Washington State’s list of impaired waterbodies. Within the last decade, water temperatures in segments of the South Fork and some of its tributaries now exceed the thresholds established for the protection of cold-water salmon populations. Of the nine salmon species present in the South Fork, three—spring Chinook salmon, summer steelhead trout, and bull trout—have been listed as threatened under the federal Endangered Species Act and are considered a high priority in restoration efforts.

In addition to the problems of warming waters, global climate change has the potential to significantly impact the freshwater ecosystems upon which salmon depend. Stream temperatures are projected to continue increasing in most rivers, and changes in hydrology, such as a reduction in summer baseflows, could potentially exacerbate these conditions.

To better understand the potential impact of climate change on achieving both regional water quality and salmon recovery goals, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency—through Region 10, the Office of Research and Development, and the Office of Water—partnered with the Washington Department of Ecology, the Nooksack Indian Tribe, and the Lummi Nation to launch a collaborative research pilot project for the South Fork Nooksack River.

The overarching goal of the pilot research project was to further EPA’s understanding of how to incorporate projected climate change impacts into a total maximum daily load (TMDL) implementation plan, using the temperature TMDL developed for the South Fork as a pilot study. The TMDL program is one of the primary frameworks for maintaining and achieving healthy waterbodies nationwide, implemented pursuant to section 303(d) of the Clean Water Act. Additionally, the collaborative framework and coordinated research components conducted as part of the pilot research project provided the opportunity to move beyond the regulatory goal of the South Fork temperature TMDL and synergistically explore how climate change might influence salmon recovery actions and restoration plans prepared in the context of the Endangered Species Act.

Applying place-based research

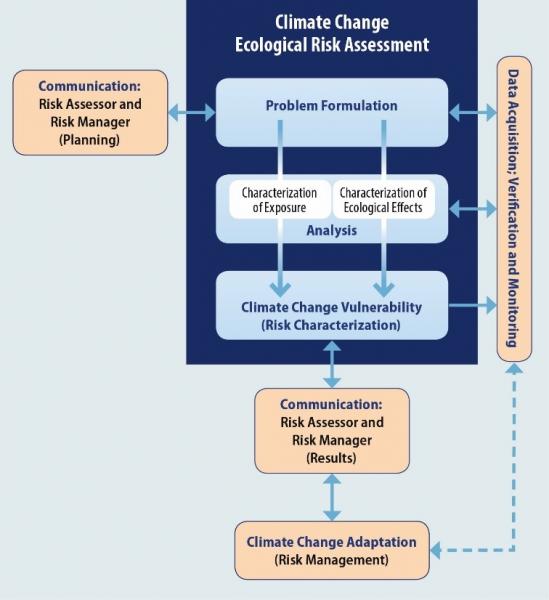

The collaborators developed an assessment containing both quantitative and qualitative information. The assessment is structured as a risk assessment in that it considers a range of climate change impacts oultined in Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) scenarios, rather than focusing on a single prediction for future stream temperature.

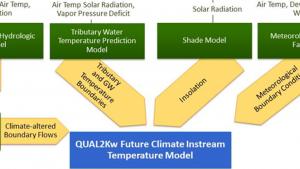

The quantitative assessment evaluates the implications of climate change using the best available climate science, using methods—such as the QUAL2Kw water quality model (see link at right, under Tools)—to estimate future temperatures of the South Fork with and without climate change for the 2020s, 2040s, and 2080s.

The qualitative assessment—which relied on stakeholder engagement as a fundamental, cross-cutting element—is a comprehensive analysis of climate change impacts on freshwater habitat and Pacific salmon in the South Fork, and an evaluation of the effectiveness of restoration tools. This aspect of the assessment used local and tribal knowledge from the Nooksack Indian Tribe to identify and prioritize adaptation strategies. The qualitative process depended on establishing deep engagement with local stakeholders, so collaborators created a network of technical experts and individuals from tribal, state, and local governments. In particular, the researchers recognized the special status of the tribal governments involved in the project. Workshops, webinars, and interdisciplinary working teams supported interactive stakeholder engagement. The group used the Beechie method, with some adaptation for the South Fork watershed, to provide a systematic, stepwise approach to analyzing climate change impacts, including evaluation by climate risk, species, and restoration action.

The combination of quantitative and qualitative assessments resulted in actionable science that supports the co-production of knowledge for climate change adaptation.

Taking action for salmon recovery

The project resulted in the identification of adaptation strategies to mitigate current challenges to salmon recovery and future impacts from climate change, and these strategies have been incorporated into the local watershed's management tools. The quantitative results include the key finding that the ability of the watershed to support shade-casting vegetation—a variable known as system potential shade—can likely provide substantial resiliency into the future.

The South Fork Salmonid Recovery Plan prioritized several strategies, including removing barriers to upstream migration, floodplain reconnection, restoring stream flow regimes, increasing cold-water refuges, reducing erosion and sediment delivery to the river, restoring riparian functions, and increasing riparian forest cover along the river and tributaries.

The proposed strategies rely on extensive coordination and outreach throughout the watershed to involve all partners, especially land owners along the river. Monitoring will be key to understanding salmon responses to climate change and how impacts may diminish as the watershed recovers. The key to adaptation will be found in successful implementation of the researchers' recommendations.