Hands-on learning

When Hurricane Matthew raged close to the Georgia coast in October 2016, residents of St. Marys, Georgia, watched anxiously. Most had already evacuated their homes—they had been warned that the city could see a 10-foot storm surge if Matthew passed by at high tide.

Fortunately, the storm’s path “wobbled” a bit and the eye of the storm moved seaward for a while instead of heading directly to St. Marys. The delay put the storm’s main impact at low rather than high tide, minimizing storm surge flooding. Before the storm had passed, though, it caused power outages, major road closures, and extensive flooding.

Despite the anxious hours watching the storm's path and the flooding and damage it left behind, students at St. Marys Middle School eventually saw it as a great hands-on learning experience. While the aftermath of flooding was still obvious in St. Marys' historic downtown, the seventh-grade students were learning about pathogens. Recognizing an opportunity, their teachers took students on a walk to look at areas of standing water where pathogens can breed.

“It’s unfortunate that something like Matthew had to happen, but it did lead perfectly into what we were talking about,” says Lori O’Brien, a teacher at St. Marys. “Matthew made the curriculum more relevant to the students because they could see flooding could bring about these kinds of pathogen-disease issues. That they aren’t just a problem in places such as Africa, that they have local significance, too.”

What the students didn’t realize as they viewed the flood’s impacts is that they would soon be participating in a public outreach effort to increase their community’s flood resilience.

Natural flood barriers, but flat terrain

Coastal areas in Georgia are fortunate to be surrounded by large areas of undeveloped salt marshlands and barrier islands. These can act as natural flood barriers, absorbing excess water that could otherwise inundate cities. Nevertheless, flooding is still a major threat because the coastal terrain is so flat. At a distance 30 miles inland from the coast, the elevation is only around 100 feet above sea level. When storms bring heavy rains to the region, rivers attempt to move the excess water across the flat land. Occasionally, however, the rivers overflow their banks or deliver additional water to locations already dealing with storm surge from the ocean.

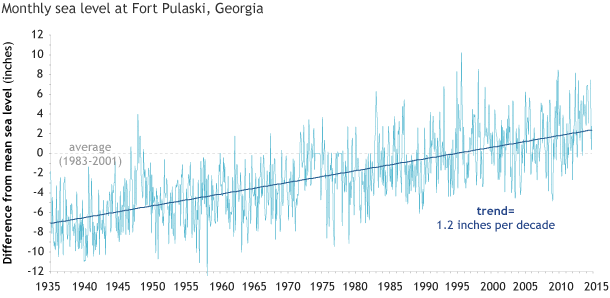

Adding to the risk of coastal flooding, Earth’s warming climate is causing sea level to rise. Since the tide gauge at Fort Pulaski—the only official tide measurement station in Georgia—began keeping records in 1935, local sea level has risen about a foot. Scientific studies show that sea level is likely to continue rising, increasing at an even faster rate. Projections indicate that sea level will rise between three and six feet by the end of the century, depending on the success of global efforts to reduce emissions of heat-trapping gases.

Encouraging communities to address flood risks

Just a few years ago, few coastal communities in Georgia were participating in the federal program—called the Community Rating System, or CRS—that rewards municipalities for lowering their flood risk. Then Tybee Island, a popular summer vacation destination, leveraged a grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Sea Grant College Program to improve their standing in the program. Island residents took steps to reduce their flood risks, and they were rewarded with an improved rating that earns them a 25 percent discount on the cost of their annual flood insurance premiums. (See the related case study Show Don't Tell: Visualizing Sea Level Rise to Set Planning Priorities.)

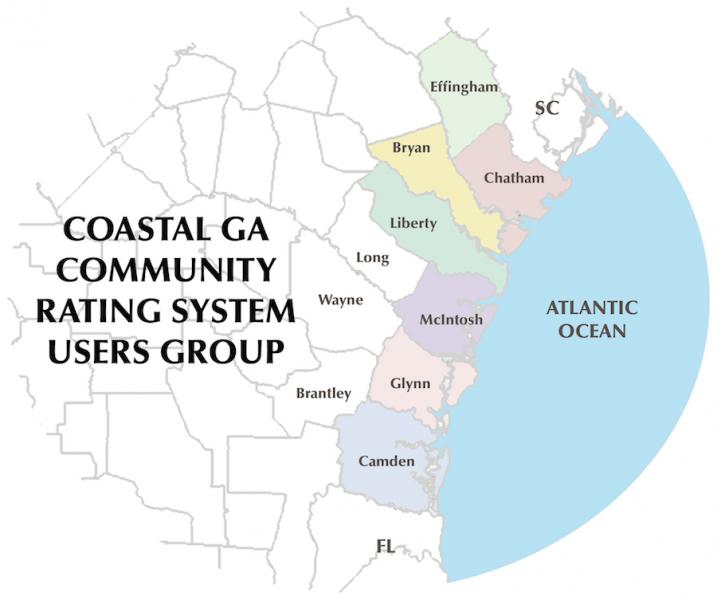

“After that, other communities up and down the coast began wondering how they could do the same thing,” says Madeleine Russell, a specialist with UGA Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant, who helps the state’s coastal communities find ways to lower their flood risk and increase their CRS ratings.

The Community Rating System is a Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) program that gives cities and towns the opportunity to earn credits for each concrete step they take to reduce their exposure to flooding. The more credits a municipality earns, the greater the savings that property owners in those communities receive on their flood insurance.

Incentivizing communities to address their risk of flooding is critical for the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). Due to damages from flooding associated with Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy in 2005, the NFIP was $24 billion in debt. The program had to raise flood insurance premiums by as much as 25 percent in high-risk areas. The only way property owners can get relief from those rate hikes is if their municipalities join the CRS and take steps to improve their flood resiliency.

Understanding how to reduce insurance costs through CRS isn’t a simple process, though, and that’s where Russell comes in. She read the massive guidebook of regulations for the CRS—all 704 pages—and translated it into plain English. “It takes a lot of careful planning and awareness and communication to understand all the nuances of how the CRS program works,” says Russell. Now, she works to help Georgia’s coastal communities benefit from her interpretation of the CRS manual. She also expanded the Coastal Georgia CRS Users Group, which gives communities a way to share their own strategies for getting CRS credit with other floodplain managers.

Targeting tweens

After Tybee Island improved their CRS rating, a number of Georgia’s coastal communities took notice, including St. Marys and Camden County. Two local employees there—Scott Brazell and Jeff Adams—decided to work on activities in the CRS’s public information category. Specifically, they choose to create what the CRS manual calls a Program for Public Information (PPI).

A PPI is an outreach effort designed to educate residents about flood hazards and resiliency. CRS gives credit for PPI because research has shown that well-informed people make better decisions about flooding. They take steps to protect themselves and their property by retrofitting their homes, buying flood insurance, and planning the actions they will take during the next flood.

Brazell, who is the Floodplain Manager for Camden County, which includes St. Marys, and Adams, the community development director for St. Marys, came up with an interesting twist for their PPI: they decided their target audience would be tweens.

The two men had recently been asked to join a county-wide stakeholders group for St. Marys Middle School, which was applying to be a STEM school. Brazell had also been involved with teaching middle school students to use handheld tools to map the local terrain and understand the floodplain. Now, they wondered if they could help the school incorporate flood resiliency in their curriculum.

“We thought we could reach more people through the kids,” Adams says. “Kids bring this stuff home and they get excited about it and it becomes kind of a viral thing, you reach the adults through the kids.”

Compared to other rural coastal communities, St. Marys has a large number of families with school-age children due to its proximity to the Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay. Because personnel are often assigned to the base temporarily, many of the families are only there for a short time.

Considering their PPI strategy, Adams recalled, “That was another thing we were running up against. We have such a transient community, people are not aware of the threats of hurricanes or riverine flooding or sea rise. They don’t know about storm surge, just because the hurricane might not hit them directly, they could still face flooding.”

Changes in the span of a lifetime

After Hurricane Matthew, with help from Brazell and Adams, students used mapping equipment to measure low-lying areas around the school. They also took samples from standing water in these areas to test for pathogens, built water filters that could strain them out, and discussed public health threats caused by such micro-organisms. Ultimately, the students hope to develop a flood awareness education program they can present to adults in the community along with a free water filter kit.

In the meantime, Adams and Brazell put together a presentation to share with the community, including slides that illustrate how sea level rise will impact St. Marys. Already, an historic cemetery and other areas are underwater during high tide, and computer models predict that over the next several decades more parts of town will be underwater.

“In the span of one lifetime, it’s shocking to see how much change there’s going to be,” Adams says. “That’s really one of the factors that helped us decide we have to be educating the youth in this area as much as possible, in hopes that when they grow up and build homes of their own, they’ll retain this knowledge and try to put themselves in a safer position.”

Adams and Brazell will also share their work with the other members of the Coastal Georgia CRS Users Group, Russell says. “As Hurricane Matthew traveled up our coast, it became urgently important to use local messages that worked with our population and our guests, and conveyed our local vulnerabilities,” she says. “Their Program for Public Information came up with 62 local messages that can be modified or adopted by all of our Georgia CRS Communities.”