Harmful algal blooms—exacerbated by warming ocean temperatures

Harmful algal blooms (HABs) have long been a threat in southeast Alaska: the first human deaths attributed to a HAB occured near Sitka, Alaska in 1799, when an outbreak of paralytic shellfish poisoning killed over a hundred members of Alexander Baranof’s crew. An HAB event occurs when nutrients and sunlight are just right and plankton species respond by multiplying especially rapidly. Submarine filter feeders such as clams, cockles, and scallops that take in the plankton can become contaminated with natural, algal-derived toxins. When people eat these shellfish, the toxins can lead to sickness, brain damage, and death.

Increasingly, evidence suggests that warmer ocean temperatures associated with climate change have contributed to worldwide increases in the duration, frequency, and geographical distribution of HABs. As ocean temperatures rise, increases in HAB outbreaks are expected to worsen over the next few decades. In response, researchers, shellfish growers, and managers must begin to investigate adaptation strategies that can increase their resilience and their capacity to endure climate-driven changes in HAB events. The development of successful adaptation strategies will require an understanding of where and when HABs are likely to occur in a warmer climate.

A partnership to monitor HABs

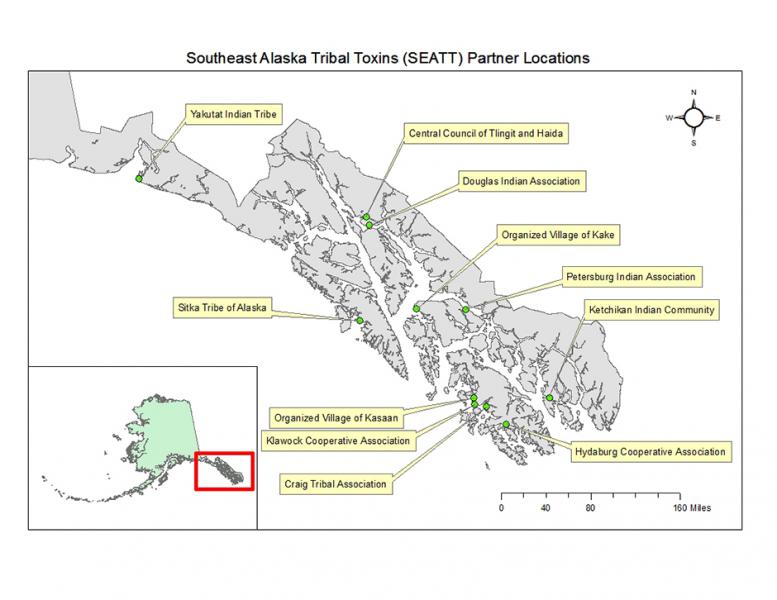

Although the State of Alaska regularly tests commercial shellfisheries for toxins, they do not test recreational and subsistence shellfisheries. Toxin levels on beaches used for recreational purposes are also unmonitored. In October 2013—after two cases of paralytic shellfish poisoning in Sitka—regional tribal communities formed the Southeast Alaska Tribal Toxins (SEATT) partnership to combat the risks of HABs to subsistence shellfish harvesters.

The SEATT partnership seeks to bring tribes in southeastern Alaska together to assess the beaches and shellfish that the state cannot test, increasing access to subsistence resources for tribal members. To date, 11 of the 17 Tribal Nations located in southeast Alaska have joined the partnership. Training and technical assistance for the SEATT partnership is provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) Marine Biotoxin Programs in Seattle, Washington, and Charleston, South Carolina. Additional technical support comes from the Washington State Department of Health Biotoxin Program, the University of Alaska Fairbanks School of Ocean Fisheries and Science, and the Southeast Alaska Regional Dive Fisheries Association. Funding for this partnership has been provided primarily by three federal sources: the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's Indian General Assistance Program, the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs' Climate Change Program, and the Administration for Native Americans' Environmental Regulatory Enhancement Program.

Eyes on the water

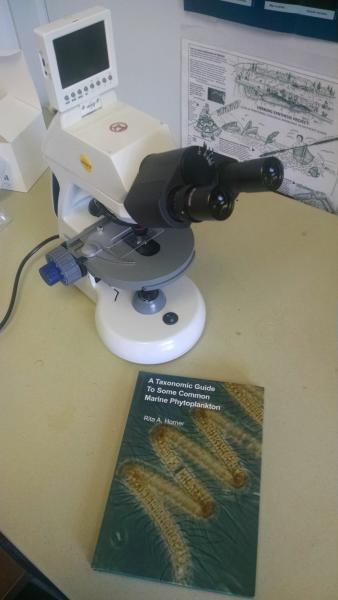

At workshops organized through the SEATT partnership, environmental staff from participating tribes learn to use phytoplankton nets, filtering apparatus, and identification tools. Manuals and training resources are distributed via DVD to participating tribes and area communities. These resources can also be accessed from the Southeast Alaska Tribal Ocean Research website (see link in sidebar, under Additional Resources).

Baseline data collection includes weekly phytoplankton species identification and quantification, collection of filtered water samples to analyze for cellular toxins, and recording of environmental parameters. In addition to hosting recorded data on the partnership's website, data is also included in the NOAA SoundToxin Database and the Phytoplankton Monitoring Network to help track the growing threat nationwide.

With “eyes on the water” each week, SEATT members can advise their communities of the potential dangers of local shellfish. Each SEATT community uses the data collected to assess both their local and regional vulnerability to HAB events.

A new testing laboratory saves time and money

By mandate, shellfish tissue must be analyzed within seven days of sample harvest. For southeast Alaskan commercial harvesters, there was no local laboratory that could consistently meet the stringent requirements; samples had to be sent to Anchorage for the required testing. Sample collection, transportation to a lab in Anchorage, and lab analysis can take three to four days, without weather delays—delays that are commonplace in southeast Alaska. Additionally, the boat and plane transport needed to carry the samples is expensive.

To better serve southeast Alaskan commercial shellfish harvesters—as well as to provide the first opportunity for subsistence shellfish harvesters to test their beaches—the Sitka Tribe of Alaska plans to open a shellfish testing laboratory, already in development. The lab will be able to text for toxins using non-regulatory methods by the end of 2015, and will be ready for testing on a regulatory level in the spring of 2017. This new lab will use a recently approved Interstate Shellfish Sanitation Conference (ISSC) receptor binding assay to assess the toxin levels in shellfish. The lab will also be used to conduct regulatory sampling using additional techniques for more species and concerns over time.

Benefits and future expansion

Knowing with confidence when traditional marine foods like shellfish can be harvested safely allows southeast Alaska tribes to continue to enjoy this important cultural icon. Perhaps more important than simple enjoyment, however, is the increased access to local food sources. Subsistence food is relied on heavily in southeast Alaska, where the cost of imported goods is high. As Sitka Tribal Chairman Michael Baines notes, "The Sitka Tribal Council is very concerned about rising ocean temperatures, but is very pleased to have the Tribe's new lab and its ability to detect harmful algal blooms and associated toxins in traditional foods."

The weekly plankton monitoring is being developed into a forecasting tool in which rising water temperatures can be linked to thresholds when HAB events become more likely. A proposal has been submitted for additional Bureau of Indian Affairs climate program funding to map algal cysts beds to determine HAB potential and additional control options. Results will be used to develop subsistence shellfish management plans based on sampling data. Coordination has begun with local and state health departments to improve awareness of the dangers of untested shellfish.

The growing number of tribes involved in the SEATT partnership can also leverage their experience with the partnership as they begin to face other climate impacts together. Using their diverse experiences, they may be able to generate innovative solutions to a variety of problems linked to the rapid warming of lands and waters being experienced in southeastern Alaska.