Alaska's 33,904 miles of shoreline (more than four times that of Florida) means that the marine environment plays a critical role in the state’s economy and traditional way of life. The state's high-latitude setting also makes it vulnerable to rapid environmental change.

Many Native Alaskans depend on subsistence harvesting both for cultural practices and for survival. According to NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service, more than 55,000 jobs in Alaska are supported by the seafood industry. In 2015, the industry contributed $2.4 billion to Alaska's gross domestic product.

Across the seafood industry, shellfish aquaculture produces more than $600 million worth of sustainable shellfish each year and supports tens of thousands of jobs in coastal communities throughout the United States. While shellfish aquaculture is helping to meet increasing consumer demand for sustainable seafood, the industry is at risk from ocean acidification—a human-caused environmental change.

Key stressor: Ocean acidification

Ocean acidification is the result of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere mixing with and dissolving into the ocean. The result is a chemical reaction that lowers the pH of seawater, moving it toward the acid end of the scale. As people around the world burn fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and gas to power their cars, airplanes, ships, and power plants, emissions from those processes increase the amount of carbon dioxide in the air. Earth's ocean absorbs about one-third of the carbon dioxide emitted into the atmosphere. Therefore, as carbon dioxide increases in the atmosphere, it also increases in the ocean.

The observed increase in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and oceans over the past half-century is changing the chemistry of the ocean, resulting in an increased concentration of hydrogen ions in seawater, making it more acidic. As the oceans become more acidic, carbonate ions (the critical building blocks for shelled animals such as crabs, clams, and coral) become less abundant.

When water chemistry is disrupted from ocean acidification, calcifying organisms such as oysters, sea urchins, and pteropods have a harder time building and maintaining their shells. As a result, they have to exert more energy to grow their shells and can, ultimately, become compromised. While shell-growing organisms are most directly impacted, all the other organisms that depend on them as food sources—including humans—can also be affected.

Over the past decade, shellfish hatcheries in the Pacific Northwest have experienced the negative impacts of ocean acidification. Some have nearly collapsed due to economic losses.

Local impact...or more widespread?

In 2012, the University of Alaska Fairbanks Ocean Acidification Research Center (OARC) and NOAA's Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory (PMEL) partnered with the Alutiiq Pride Shellfish Hatchery in Seward, Alaska, to develop a rapid response program to monitor ocean acidification impacts on shellfish.

Alutiiq Pride is the only shellfish hatchery in Alaska, and is part of the Chugach Regional Resources Division, a tribal organization focusing on natural resource issues that impact their region. The hatchery provides seed stock for aquatic farming, develops seed for new species, produces seed for shellfish enhancement projects, and conducts research.

While working with researchers from the Hakai Institute and the OARC, staff at the hatchery found that aragonite levels—the form of carbonate needed for shellfish to build and maintain their shells—was quite low in the seawater entering the hatchery. This discovery raised major concerns about whether this was limited to their location on Resurrection Bay, or if it was a regional phenomenon.

Water sampling and Burke-o-Lators

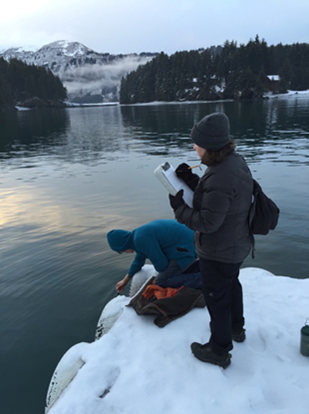

To find out, people from Nanwalek, Port Graham, Seldovia, Tatitlek, Chenega, Eyak, Valdez, and Qutekcak—all in south-central Alaska—collected water samples from their villages once a week. The two-year water sampling project was funded by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and involved two science centers, the Park Service, and seven native villages. These samples were sent to Alutiiq Pride, where technicians analyzed water from each location. Results indicate that ocean acidification is not isolated to Alutiiq Pride on Resurrection Bay. Rather, the observed trend toward acidification is part of a larger, regional transition that is becoming widespread.

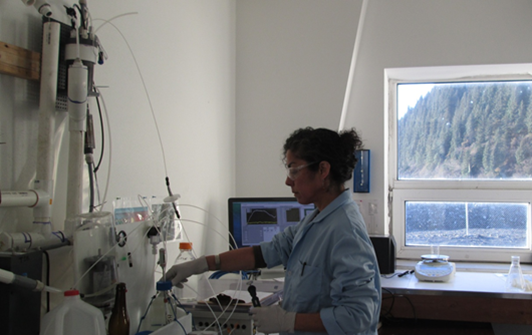

In 2014, Alutiiq Pride and four other shellfish hatchery sites located in Washington, Oregon, and California partnered with NOAA’s Integrated Ocean Observation System to use monitoring systems—called Burke-o-Lators after their inventor, Oregon State University professor Burke Hales—to measure ocean acidification at their hatcheries. This monitoring system populates data streams from each of the sites in a portal that provides critical environmental intelligence information to researchers, coastal managers, and end users such as shellfish aquaculture farms. In this case, the Alaska Ocean Observing System maintains the portal that hosts the Alutiiq Pride ocean acidification data. The goal is for the monitoring information to support adaptation strategies and other decision-making efforts along the coast to keep the hatcheries sustainable into the future, even as ocean acidification continues.

Moving forward

Alutiiq Pride also conducts their own ocean acidification research with partners from the University of Alaska Fairbanks and other research centers. Currently, Dr. Amanda Kelley, Co-Director of the Ocean Acidification Research Center, works with the hatchery to research the effects of ocean acidification on shellfish. Kelley and her team are testing the resiliency of three Alaskan subsistence species: the butter clam, basket cockle, and littleneck clam. Specifically, they are running experiments to see how changes in ocean chemistry impact the larvae of these species. The larval stage is when these animals are putting on their shell and are most sensitive to the effects of ocean acidification. The researchers plan to continue their experiments on abalone and red king crab in the coming years. Ultimately, they hope to test the resiliency of all the shellfish species they raise to different levels of ocean acidification intensity and see the effects on these organisms.

Alutiiq Pride is using the information gathered from these studies to determine the tipping points at which aragonite (carbonate) levels are too low and thus require the hatchery to take mitigating steps to keep their animal stocks healthy. In particular, they can “buffer” the water by adding soda ash, which artificially raises the pH of the seawater to be less acidic and thereby counteracts ocean acidification. Other hatcheries are already using soda ash as a mitigation technique to reduce the negative impacts to their shellfish stock. As Alutiiq Pride is part of a tribal organization, they want to know what the impacts of ocean acidification could be on this food source for villagers, and whether it could be a factor in villages that experience declines in shellfish populations.

While mitigation measures such as soda ash help reduce the effects of ocean acidification on shellfish, reducing human-made fossil fuel emissions will be essential in reducing the trend toward ocean acidification. Initiatives of groups like Alutiiq Pride and NOAA to understand the causes and impacts of ocean acidification will provide critical information for communities to develop resilience and adaptation strategies.