An evacuation notice in the middle of the night

As large waves washed over the seawalls of Majuro in the pre-dawn hours of Monday, March 3, 2014, police banged on residents’ doors, telling them that their properties were flooding and that they needed to evacuate.

“I was in bed at home, as most people were, because it was 3 a.m.,” recalls Angela Saunders, who was awakened by a phone call from a colleague alerting her to the high swells.

Majuro, built on a coral atoll, is the capitol of the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI). Sitting roughly 10 feet above sea level, it’s composed of several land segments connected by a shallow reef encircling a lagoon.

The frequency and magnitude of coastal flooding events on Majuro and nearby atolls have increased significantly over the last decade and, as sea levels rise due to climate change, such events will likely become even more frequent. Seawater flooding in low-lying communities can threaten public health and safety by displacing residents, contaminating fresh water supplies, ruining crops, damaging infrastructure, and spreading disease.

Surveying the damage

By 5:30 a.m., high tide had come and gone and the flooding had temporarily subsided. Saunders—head of the Majuro sub-office of the International Organization for Migration, a group that responds to coastal flooding—left her house to survey the damage. “There was still a fair amount of water on parts of the road,” she said. “We were driving though maybe a foot of water in some places. People were already cleaning up by the time we got there.”

Over the radio, the government warned that the high seas could last for the next two days, becoming especially dangerous during high tides. Many thought that the night’s waves were the result of the highest tide of the year, a predictable event that occurs when a full moon is close to Earth. But months later, after scientists analyzed the year’s tides, they determined that was not the case.

In fact, rather than being an astronomical highest-tide-of-the-year event, the March 3rd event resulted from distant storms north of RMI near Japan. The storms caused large waves that were exacerbated by high tide. The flooding was particularly bad because the waves had come from both the lagoon and ocean sides.

Shelters offer meals, desalinated water

After attending a national disaster meeting, Saunders and others who work for organizations that respond during emergencies headed out to assess the conditions in Majuro’s emergency shelters. Schools, a college, churches, and other facilities were being used as shelters for close to 1,000 displaced citizens. Another 250 people were relocated to shelters on Arno, Majuro’s less-populous neighboring atoll.

Workers served meals and filled bottles with desalinated water in case the flooding further compromised fresh water resources. “The classrooms had been cleared out, and people were sleeping on the floors,” said Victoria Bannon, representative of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies.

Building berms as part of the solution

Meanwhile, in anticipation of the evening high tide, the government built berms with bulldozers to protect the coastline. As high tide approached, radio announcements warned residents to stay clear of the shore. “People were still relocating to shelters, just to be safe,” said Saunders.

The high tides and large waves eroded most of the new berms, which were made of poorly consolidated fine material, such as sand. Those constructed of coarser aggregate material—such as sand, gravel, and rock—fared better.

“The idea behind berms is that they’re migratory. So they’re going to move as the island moves over time—whether via natural processes or accelerated via climate variability and climate change,” said Karl Fellenius, a former coastal management extension agent for the University of Hawai'i Sea Grant College Program in Majuro.

Berms are part of the natural topography of atoll islands, but in Majuro they have been modified or eliminated through development. Rebuilding them using mixed-grain materials, plus compacting and vegetating them, would provide some flood protection, Fellenius said. “But," he added, "they’re not intended to stop the island topography from changing.”

Better communication can enhance protection

The aftermath of the flooding showed that berms alone are not an effective solution to coastal flooding. “We need to find a balance between a reasonable level of prevention coupled with a more effective early warning preparedness and response system,” said Bannon.

The March 3rd event illustrated her point. Most residents did not realize that the swells were approaching until the waves reached their doorsteps at 3 a.m. “It’s not only the timing that must be improved,” she said. “It’s the content of the warning. It needs to be issued hand-in-hand with some recommendations for how communities can use that information. For people in certain areas, is it recommended for them to protect their property by sandbagging their doors, or to evacuate?”

Early warning pilot project

The day after the flooding, officials found that more than 100 homes were damaged. Doors and windows were broken, and debris had washed inside. By that evening, most families had returned to their homes.

Ten months later, in January 2015, several groups (see list of Partners at right) came together to start a project to address the need for a comprehensive early warning system. They began by assessing how the existing weather and climate-related services could be better used and communicated to residents. Then they worked with the national disaster response framework to set up a community-based early warning system so that people are notified and also have a plan for responding to different hazards. The Finnish-Pacific Project (FINPAC), a four-year regional project funded by the Government of Finland, supported the project.

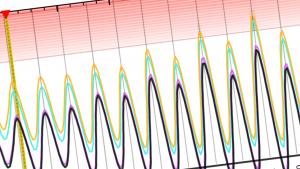

The project was one of several to address early warning for potential hazards. Another is a new weather forecasting tool that gives a more accurate analysis of the tides and can help predict potential inundation events. The Pacific Islands Ocean Observing System at the University of Hawai'i is developing the tool. Building new partnerships and leveraging existing ones will help residents of Majuro and the RMI to better cope with climate change and future coastal flooding events.