Importing seafood is big business

Fishermen across Central America and in the Caribbean—a region known as Mesoamerica—ply the waters of the Atlantic and Pacific to make a living and provide food to eat and sell. The United States is a lucrative trading partner for these fishermen—we import 90 percent of the seafood we consume, about half of which comes from aquaculture.

Stressors and impacts

Some phytoplankton species produce toxic chemicals, but they are not usually present at high enough concentrations to affect human or animal health. When populations of these phytoplankton species grow rapidly, however, they can produce large quantities of toxins and decrease oxygen availability in the water, posing a threat to marine life and humans that come into contact with the water. These incidents are known as “harmful algal blooms” (or HABs).

Fish and shellfish can accumulate toxins released by HABs. If humans ingest even a small amount of this contaminated seafood, they can experience serious health problems. News reports, or even rumors, of possible seafood contamination can scare off potential buyers. Today, it is estimated that HABs impact the U.S. economy by $82 million per year.

In coming decades, climate change and other related stressors may increase the frequency, severity, and geographic distribution of HABs. Warmer water temperatures, increased nutrient runoff after severe storms, and higher atmospheric carbon dioxide can promote growth of HABs. Thus, in addition to the threat of human health impacts, HABs present an economic threat to Mesoamerican fishermen and U.S. importers who depend on the seafood trade for their livelihoods.

SERVIR helps keep our seafood supply safe

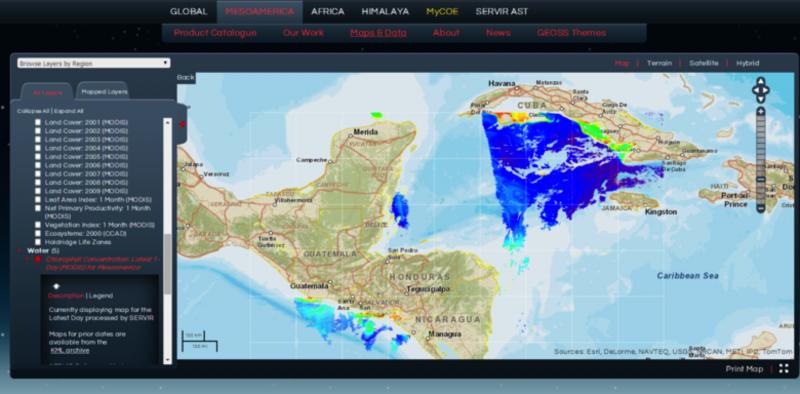

SERVIR is a regional visualization and monitoring system developed by NASA and the U.S. Agency for International Development. One of its purposes is to help governments monitor the locations and extent of HAB-contaminated areas. The site shows daily updates of sea surface temperature, chlorophyll-A, and fluorescence line height data from NASA’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS); these data provide accurate information about the location and extent of HABs.

The SERVIR system helps fishermen avoid sites contaminated by HABs, thus protecting their livelihoods and helping to keep the food supply safe for local and international buyers. Officials estimate that the use of SERVIR has saved millions of dollars for the tourism and fishing industries.

References

-

Dale, B., M. Edwards, and P.C. Reid, 2006: Climate Change and Harmful Algal Blooms. Ecology of Harmful Algae, E. Granéli and J. Turner, Eds., Ecological Studies, Vol. 189, Springer-Verlag, 367–378.

-

Fu, F.X., Y. Zhang, M.E. Warner, Y. Feng, J. Sun, and D.A. Hutchins, 2008: A comparison of future increased CO2 and temperature effects on sympatric Heterosigma akashiwo and Prorocentrum minimum. Harmful Algae 7, 76–90.

-

Hoagland, P., and S. Scatasta, 2006: The Economic Effects of Harmful Algal Blooms. Ecology of Harmful Algae, E. Granéli and J. Turner, Eds., Ecological Studies, Vol. 189, Springer-Verlag, 391–402.

-

NOAA FishWatch, cited 2013: Sustainable Seafood—The Global Picture, Farmed Seafood Imports to United States.