An "eye-opening experience"

Deke Arndt’s “State of the Climate” briefings usually dwell on graphs of U.S. and global temperature and precipitation trends. But for the November 2016 report, the head of monitoring for NOAA's National Centers for Environmental Information found his slides competing with first-hand evidence: smoke from the worst wildfires in decades was drifting through the streets surrounding the event’s conference room in Asheville, North Carolina. Questions from briefing attendees strayed into unfamiliar territory for Arndt, who is less comfortable connecting specific events with global warming, so he chose his words carefully: “You combine drought and arson and it can be pretty significant,” he replied.

“Pretty significant” turned out to be a good turn of phrase. Just a few weeks before, a team of researchers with UNC Asheville’s National Environmental Modeling and Analysis Center (NEMAC) had identified wildfires as one of the main climate-related threats facing the 90,000 residents of the city. The team is helping develop a resilience assessment to shore up the city’s capacity to adapt to those changes using the U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit.

Amber Weaver, the city’s sustainability officer, calls the fires “an eye-opening experience for both city staff and consultants,” one that poses “a present and tangible emergency.” Indeed, what foresters called the worst fire in a century consumed more than 7,000 acres, including a large section of Gatlinburg, a popular tourist destination just across the Tennessee border. No matter what specific actions the resilience assessment eventually calls for, addressing the risk from fires is sure to be a major element.

From fire to floods

Another major threat is also fresh in the minds of residents of the region. In 2004, when tropical storms Ivan and Frances dealt the area a double blow, city officials had to deal with major flooding. Eleven people died and 140 homes were destroyed in western North Carolina as a result of flooding and landslides following heavy rains. In Asheville, the Swannanoa River was overwhelmed; the flooding that resulted caused widespread damage to homes and businesses, and triggered a significant loss of economic revenue for the city from the interruption of day-to-day commerce.

“2004 was significant for Asheville, especially with regard to flooding and landslides,” says Karin Rogers, a research scientist and director of operations for NEMAC. “There’s been more awareness in the last 10 to 13 years.”

It was similar to the catastrophic flood of 1916, which was also the result of the convergence of two storms in space and time. The National Weather Service reported that the region received the largest 24-hour rainfall in U.S. history: one spot near Grandfather Mountain measured more than 22 inches of rain in 24 hours. Some stretches of the French Broad River, which often has trouble supplying enough water for paddlers, tripled in width to 1,300 feet. Eighty people died.

Extreme rainfall events such as these fit with a trend toward increased heavy precipitation across the country. According to the Third National Climate Assessment, extreme precipitation in the southeastern United States increased by 27 percent from 1958 to 2012.

Local challenges—and opportunities

Dramatic events such as rising seas, storm surge, extreme drought, or Arctic ice melt may come to mind when people think about the global impacts of a changing climate. Asheville’s inland location, temperate climate, and elevation of 2,133 feet above sea level (at last count) doesn’t mean, though, that its residents can afford to take the subject any less seriously.

The list of possible climate hazards for even a medium-sized mountain community like Asheville can be long, complex, and hard to model. "Understanding what impacts Asheville faces took longer than we expected,” says Matt Hutchins, a research scientist who’s also part of the NEMAC team. "It's difficult to compare cities in different parts of the country. Rather than taking the approach of comparison, we considered the people and assets that make Asheville unique and how they could be affected by climate-related threats," he added. Even though Asheville—and cities like it across the country—are fortunate enough not to face some of the extreme impacts associated with coastal, desert, or arctic areas, there is no reason for complacency. Places like Asheville have options and opportunities for building resilience.

For instance, it would be a foolish not to use the expertise of the scores of scientists like Deke Arndt who happen to work in the city at NOAA's National Centers for Environmental Information. There’s also a growing pool of private-sector consultants loosely organized by a year-old innovation center called The Collider. Its members share a mission of “catalyzing market-driven climate solutions” in a world spending upwards of $300 billion annually on climate adaptation.

The partnerships that have evolved in the Asheville climate science community—Amber Weaver calls them “instrumental” as the city works through its climate resilience planning process—may in fact be one of the city’s most valuable assets. Weaver herself is a case in point: few cities of Asheville’s size have a dedicated sustainability officer.

Using the Steps to Resilience

In developing the series of climate resilience planning workshops, the NEMAC team chose to use the Climate Resilience Toolkit's Steps to Resilience framework.

Following Step One: Explore Hazards, the NEMAC and city teams came up with three primary stressors: heavy precipitation (which can cause flooding and landslides), drought (leading to water shortages and wildfires), and temperature variability (with extreme heat events).

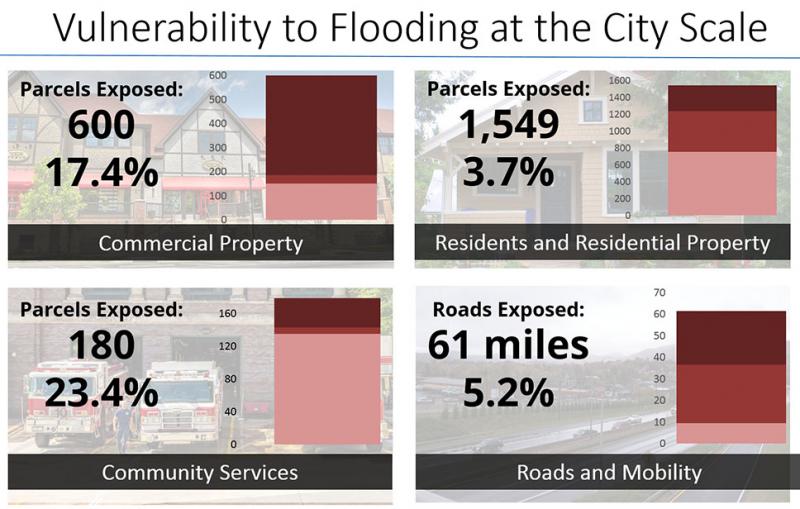

In the second step—Step Two: Assess Vulnerability & Risks—the teams identified which of the city’s physical assets are most vulnerable. For flooding, nearly four percent of Asheville’s residential properties are vulnerable to an event similar to the one the city experienced in 1916, but that number rises to more than 17 percent for commercial properties. As for the threat posed by wildfire, of the assets evaluated, residential properties are the most exposed (located where they could be adversely affected).

By the spring of 2017, the 14 city departments involved in the assessment were digesting that information and had begun the third step: investigating the options to address the threats (Step Three: Investigate Options). The final two steps, prioritizing actions and implementation, are scheduled to be addressed later in the year.

Cross-jurisdictional collaboration and broad applicability

Among the most consequential discoveries of the process so far, according to both city staff and their partners at NEMAC, is the need for cross-jurisdictional collaboration. As the city’s sustainability director, Weaver recognizes there’s only so much Asheville can do on its own. “Many of the asset-threat pairs we identified require innovative solutions, many of which are outside of government control and therefore will require fostering partnerships with other stakeholder groups.”

For example, extreme climate events far from Asheville can lead to disruptions in pipelines that supply gasoline to the region. Adapting to these types of issues will take more than revamping emergency response protocols or rezoning at-risk neighborhoods. The good news, adds Weaver, is that resilience tends to improve when there are more partners involved.

Weaver says she was also surprised by how well the planning participants were able to collaborate, despite the disparate departments’ agendas and perspectives. “It really does take a team to be able to analyze best, next steps and options to make a city more resilient.”

For the NEMAC team, the process has also turned up some surprising findings, not all of which can be incorporated into the final plan. Unlike cities that are anticipating depopulation trends as real estate values collapse in more vulnerable areas, Asheville might find itself on the receiving end of migration patterns. “What I find interesting to consider is what does this mean for people who want to move here?” asks Rogers. “It’s hard to analyze and map, but important to consider when talking about long-term resilience.”

At the very least, Asheville’s experience with climate resilience planning is hammering home just how interconnected the community has become. The city’s assets—geographical as well as intellectual—can’t easily be reproduced elsewhere. But, suggests Rogers, the lessons being learned from studying a variety of threats and how they might impact a city’s valued assets are applicable to a broader range of cities in other regions.