Stressors and impacts

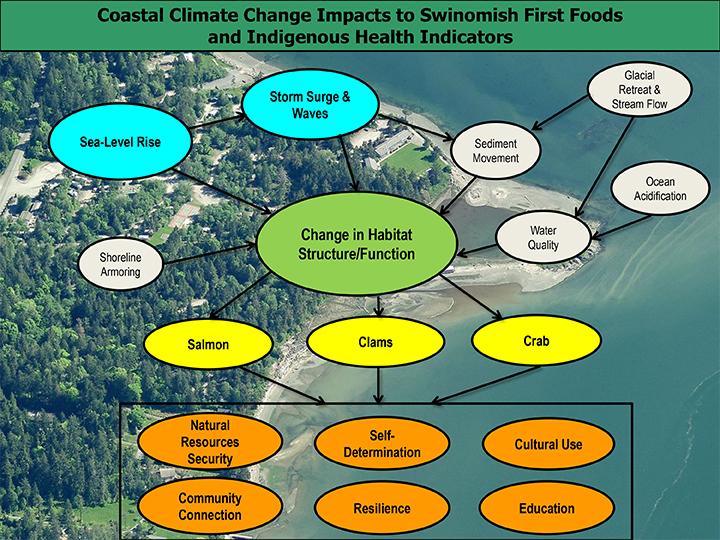

Indigenous communities of the Pacific Northwest have a saying: “When the tide is out, the table is set.” Salmon, crab, clams, and other species that use nearshore habitats—areas of the beach extending from the shoreline to the low water zone—are important as a food source for these tribal communities, but they are equally important culturally. These “first foods” are part of an extensive network of values, beliefs, and practices integral to the success of ceremonies, gatherings, education, and traditional sharing and reciprocity networks.

The combination of projected sea level rise, an associated increase in wave energy, and shoreline development are predicted to change coastal ecosystems that have supported the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community and other Pacific Northwest indigenous peoples for millennia. When the habitats that support production of these foods are impaired, the resulting negative effects amplify and reverberate throughout the intertwined social, cultural, mental, and physical aspects of Swinomish life.

Indigenous communities along the coast are disproportionately vulnerable to sea level rise and other projected climate change impacts—tribes with reservations cannot move when these impacts occur. Reservations in coastal lowlands are subject to inundation, and tribes’ treaty-protected fishing traditions are threatened by degraded aquatic habitats and loss of valued species.

Evaluating projected impacts on ecosystems and on community health

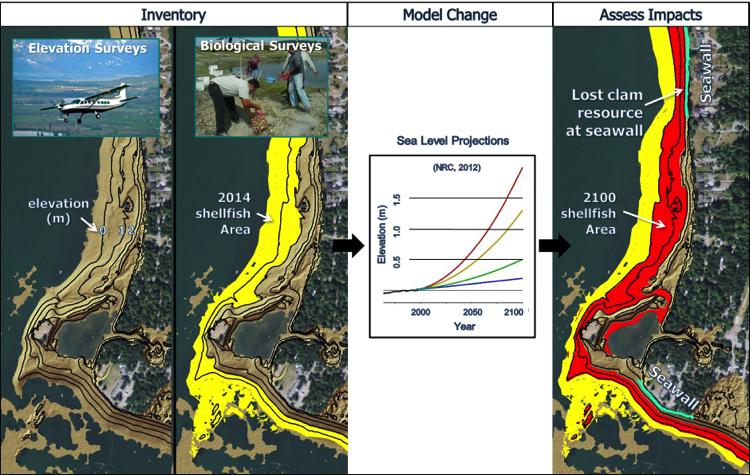

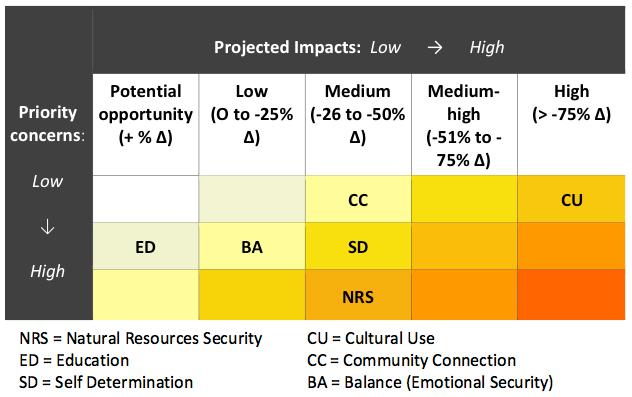

Recognizing what is at stake for their community, the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community, in partnership with the U.S. Geological Survey and the Skagit River System Cooperative, are developing tools that assess future projections of sea level rise and wave impacts to nearshore habitats. Community members will take an active role in determining community health impacts based on the projections using the Indigenous Health Indicators (see link at right). The Swinomish community will use methods they piloted and tested in 2013 to (1) assess future impacts to shellfish, juvenile salmon rearing habitats, and other culturally important nearshore areas, and (2) evaluate community health implications based on the projected nearshore impacts. Results will guide decision making to mutually benefit ecosystem protection and restoration, coastal hazards mitigation, community health, and adaptation to climate change.

The project results will provide the Swinomish community with the best available science to make challenging decisions in the face of climate change. Should the Swinomish promote retreat from dynamic shorelines, allowing beach and coastal ecosystem migration? Or should they instead “hold the line” to protect infrastructure and private property with seawalls and armoring, at the possible expense of ecosystem degradation?

The methods and tools developed for the project will be replicable by other tribal communities as they assess potential impacts and prioritize action plans to better sustain indigenous traditional foods, habitats, associated practices, and access to these resources.

Adapting to an uncertain future of dynamic change

Although planning for coastal climate adaptation makes use of best available science, the ideal plan will be a “moving target” as community members with diverse concerns navigate potential solutions to climate change in light of ongoing and legacy land use impacts. Employing accurate measures that monitor and evaluate ecologic and cultural health in tandem is paramount to addressing the complex climate change challenges that face coastal communities. The Swinomish Indian Tribal Community and other tribal communities in the Pacific Northwest are actively developing climate change adaptation strategies that integrate science and traditional knowledges in order to protect and restore ecologic, cultural, and economic resources. (For more information on traditional knowledges, see the Guidelines for Considering Traditional Knowledges in Climate Change Initiatives tool and the Tribal Nations topic discussion.)