Extreme weather can threaten water supply

Flowing rivers reduced to dry channels. Dairy cows that produce less milk. And residents who normally rely on well water filling up plastic jugs from hoses at public libraries and fire stations.

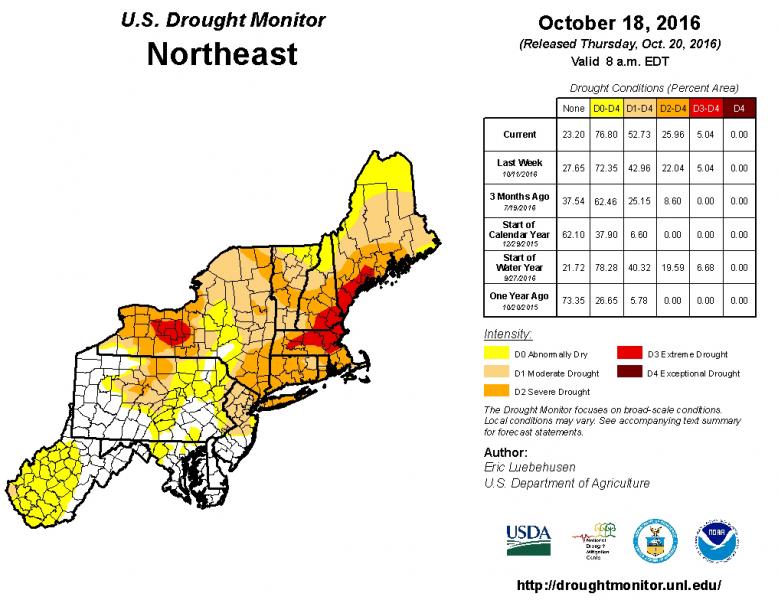

This was the scene in New Hampshire during the fall of 2016, when a severe drought struck areas of the Northeast. Though a formal attribution study of the drought—a study that can tell us how much of the credit or risk for an event should go to global warming and how much should go to natural weather patterns or random climate variability—has not yet been completed, some water-supply professionals are concerned that the drought may be connected to climate change.

The Third National Climate Assessment released in 2014 notes that drought and heavier storms will increase in the Northeast as the planet continues to warm. As evidence, the report cites that precipitation falling during “very heavy precipitation events” increased by more than 70 percent between 1958 and 2010 in the region. It also notes that increased temperatures—which cause greater evaporation and earlier spring and winter snow melt—will bring more droughts.

The summer of 2016, therefore, with its dismal rainfall and many 90°-plus days, seemed like a harbinger of what’s to come. The drought stressed both natural water resources and those of city water managers, raising concerns that the region’s water sector will become less resilient over time.

Water supply vulnerabilities

Keene, New Hampshire, has been a leader in climate change planning and mitigation. For nearly a decade, city officials in the picturesque hamlet have been planning for climate change and the extreme weather it brings, putting special emphasis on efforts to protect their water supply.

For instance, they’ve identified and prohibited further development in and around the city’s 200-year floodplain, and they’ve also adopted new design standards that require extra space for snow stacking during winter. In addition, they’ve conducted numerous vulnerability assessments, as well as updated capital improvement and hazard mitigation plans.

Still, one of the key vulnerabilities that city leaders needed to explore further was the future of their water assets. The city gets its water from two reservoirs, built in 1910 and 1931, that are located outside the city limits, and from two well-fields that supplement its surface water supply. Studies have shown that prolonged drought combined with more intense storms and large amounts of run-off can impact the overall volume, turbidity, and total organic carbon (TOC) concentration of municipalities’ water supplies.

Risk assessment tools for water managers

To better prepare for extreme weather events and their impact on the water supply, Keene water department officials Donna Hanscom, Aaron Costa, and Ben Crowder, along with a group of water department staff, spent six months in 2016—from February through July—working with officials from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Through a series of calls, webinars, and one in-person event, agency officials and city water managers walked through a climate change risk assessment process.

A key component of the process was using the EPA’s Climate Resilience Evaluation and Awareness Tool (CREAT)—specialized software designed for water managers. Users can apply pre-packaged climate data within the tool, or they can add their own climate data for improved accuracy.

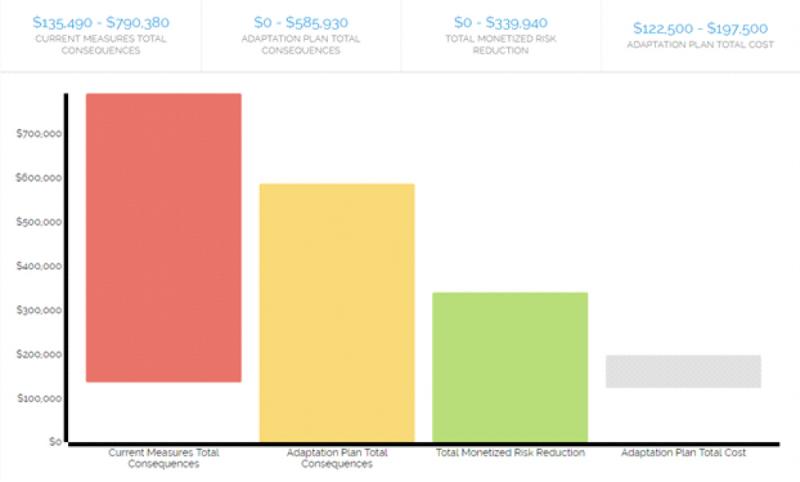

When selecting their data, Hanscom, Costa, and Crowder realized that one of CREAT’s weather stations is directly on a dam within the city limits. Even though this data was highly localized, they wanted to make their dataset even more specific by including additional statistics that measured precipitation from different perspectives. To do that, they included statistics from a 100-year and 500-year storm dataset, as well as monthly precipitation measurements, in addition to the pre-set annual precipitation dataset. At the end of the exercise, CREAT generated a comparison of the potential costs of climate change impacts versus costs of implementing adaptation measures.

In a one-and-a-half day exercise, Keene’s water utility managers and engineers were able to assess the utility’s vulnerability to extreme rainfall events—both a 100-year and a 500-year storm scenario—as well as prolonged periods of drought on their reservoir’s turbidity and total organic carbon levels. The results raised some concern in the water department, because they have already seen their TOC concentrations double during high rainfall events. Increased TOC levels require more chemical treatments to clean the water, which produces extra waste.

Planning for implementation

Keene’s water utility is planning to implement some of the adaptation strategies identified through the CREAT process in the coming years. For example, Keene is working on a watershed management plan to analyze the effectiveness of efficiency and conservation measures during drought. They are also analyzing overall water yield. Additionally, the team is looking at alternative treatments to address turbidity and TOC problems, and to reduce the amount of water lost in sewers due to frequent cleanings of the filters. Finally, Keene plans to focus on the extreme weather effects related to wastewater in a future assessment using CREAT.