Many shoreline landscapes, one setback policy

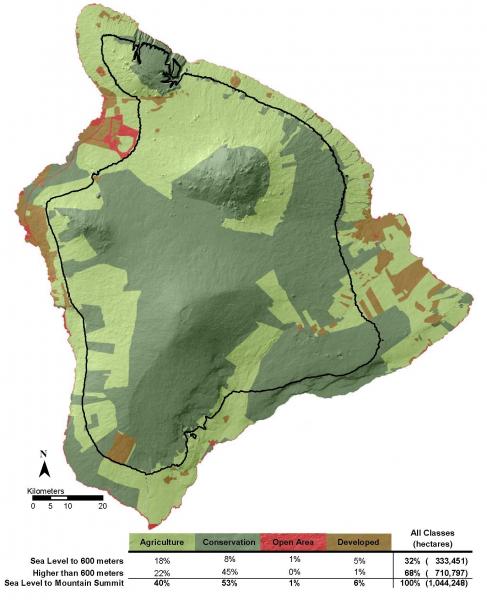

The island of Hawaiʻi—the largest and the southeasternmost of the Hawaiian Islands—is home to a diverse range of cultures, species, ecosystems, climate zones, and shorelines. Its coastline is surprisingly long, comprising more than a third of the state’s total coastline. In fact, only eight states in the nation have coastlines longer than that of Hawaiʻi Island.

The island's lengthy coast displays a range of features, including beaches, palis (steep sheer cliffs), and rugged lava formations. Rocks formed by lava take many forms around the island, and the flows range in age from half a million years to less than one year old.

In spite of the variation along the coast, Hawai'i County's initial general plan required a development setback distance of 40 feet from the established shoreline across the entire island. This largely arbitrary line did not account for different uses of the land, nor the constantly shifting environments distinct to each type of shoreline. Ultimately, it left some communities exposed to coastal hazards. The blanket policy applied over the entire island simply didn’t fit with the reality of the coast’s wide-ranging responses to the increasing effects of climate change.

Recognizing a need for research

During a 2016 meeting with staff from the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo (UH Hilo), Bethany Morrison and April Surprenant—two long-range planners with the County of Hawaiʻi Planning Department—brought up the urgent need for research to support a more comprehensive and effective coastal development setback policy. Surprenant and Morrison were concerned that the current policy was inadequate to protect the natural coastal environment and ensure human safety from processes such as coastal erosion, slumping (landslides), subsidence (sinking of land), and sea level rise. To account for the full range of physical processes that perpetually alter the shoreline at varying rates around the island, the planners encouraged the county—encompassing all of Hawaiʻi Island—to invest in cutting-edge research that would help them develop a more effective and site-specific setback policy.

Collaborative team members roll up their sleeves

Pursuing the clear need for place-based setbacks, Morrison formally initiated a collaborative research project in August of 2016. The two-year project was funded by UH Hilo’s Manager Climate Corps, a manager-driven research program of the Pacific Islands Climate Adaptation Science Center that supports natural and cultural resource managers in adapting to local climate change impacts. The research team set out to quantify historic and contemporary rates of change along different types of shorelines, and then to model observed changes into the future through sea level rise impacts.

Along with other team members, Rose Hart—who had completed an undergraduate internship involving research on shoreline setback policies—served as the graduate student driving the project forward. Ryan Perroy, Associate Professor in UH Hilo’s Geography Department and director of UH Hilo’s Spatial Data Analysis and Visualization lab, applied his experience and access to innovative research equipment and methods to develop the technical foundation for the collaborative endeavor. Charles H. Fletcher III, Associate Dean and Professor, SOEST, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa and Steven Colbert, Chair and Associate Professor, Marine Science, University of Hawai‘i at Hilo also collaborated on the project.

Previous collaboration among team members significantly contributed to the success of the relatively short project in delivering useful results. The integrated professional networks were able to hit the ground running by building upon team members’ mutual understanding of distinct professional roles and, importantly, by harnessing the pre-existing trust within the team. These factors contributed to exceptional levels of productivity throughout the collaboration. Another key element that contributed to the quick uptake of the research was team agreement about the end products: team members met multiple times to discuss the scope and project outcomes to be sure deliverables could be directly and quickly utilized by planners in crafting a new setback policy. Once all participants had a clear understanding of the deliverables, Morrison, Perroy, and Hart went to work developing detailed methodologies and field schedules.

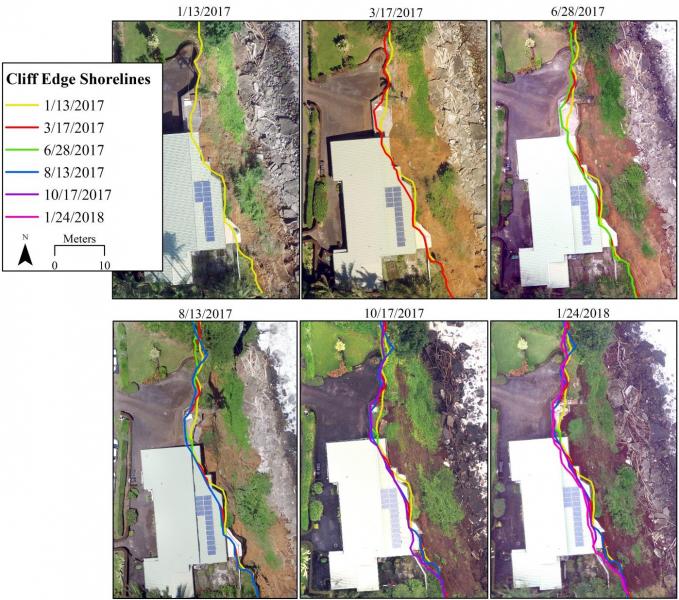

Over the next two years, the team combined existing datasets (historic aerial photos) with new data (drone imagery, topographic surveys, etc.) to quantify past and present rates of coastal change. These data were then merged with sea level rise projections and other geospatial data to estimate future impacts along the coastline using a GIS platform.

Sharing research results

In May 2018, the research team presented their findings to the County of Hawai'i Planning Department, which administers planning regulations for the entire island and provides technical advice to the county’s Mayor, Planning Commission, and County Council. Regulatory staff and the director were present, as well as private surveying companies. The stakeholders discussed coastal vulnerabilities revealed by the research, as well as additional information that would be needed to develop a science-based setback policy in the near future.

Based on analyses at Hāpuna, Honoli‛i, and Kapoho, the team offered suggestions for how the county could use scientific data to create place-based setbacks. Predictive models that combined a designated shoreline setback distance, place-based shoreline erosion rates, and structural life expectancy were suggested for calculating setbacks for locations similar to Hāpuna and Honoli‛i. Conversely, elevation-based setbacks were suggested for low-lying coastal communities such as Kapoho.

Research informs policymaking

Throughout the project, the research team worked directly with community members in each of the three study site locations. These interactions were particularly effective along the Hamakua Coast. The project became so familiar to these communities that it was directly integrated into the Hamakua Community Development Plan. A direct result of the research was a call in the Hamakua plan to generate objective guidelines for agreeing upon a practical definition for the "top of cliff,” a term in shoreline policy that has yet to be clearly defined. Developing a common understanding of this locational term is essential to monitoring and predicting erosion along unstable clifflines that can pose dramatic threats to community infrastructure.

Reality check: Hurricane Lane

In August of 2018, just after the adoption of Hamakua’s Community Development Plan, Hurricane Lane—the wettest tropical cyclone ever recorded in the state of Hawaiʻi—brought extreme rainfall to Hawai'i Island. Some communities received more than 52 inches of rain over the five-day event. The storm's heavy rains and strong winds downed trees and power lines, triggering brush fires and landslides; before it was over, the storm resulted in one fatality and $250 million in damage across the state.

Landslides observed along the Hamakua Coast were precisely the type of impacts from short-term episodic events, made worse by climate change, documented in the study of steep cliff environments. Beyond contributing to local community planning efforts, the shoreline change research effort resulted in language for the island-wide General Plan Update for all of Hawaiʻi County regarding the need for shoreline setbacks appropriate for diverse shoreline types, and the importance of accounting for long-term erosion rates, as well as episodic erosion events.

Forward into the future

Landslides from Hurricane Lane emphasized the importance of understanding the impacts of episodic events. Community members who live in areas impacted by the hurricane worked with County Council members and the Planning Department to secure funding from Hawaiʻi County, FEMA, and NOAA’s Coastal Zone Management Program to support new research into reducing risk to coastal hazards. The result is a new project, begun in fall of 2019, that aims to establish research-based shoreline and riparian setbacks for different types of shorelines. The research will build upon the foundational understanding developed in the initial co-produced research project. Together, the combined results will be utilized to develop policies that are increasingly adaptive to present and future coastal change.

Story Authors: Scott Laursen (Climate Adaptation Extension Specialist, PI-CASC) and Bethan Morrison (Planning Dept., County of Hawaiʻi)