Drought leads to a water crisis in Salinas

Salinas, a municipality on the southern coast of Puerto Rico, has a history of water concerns.

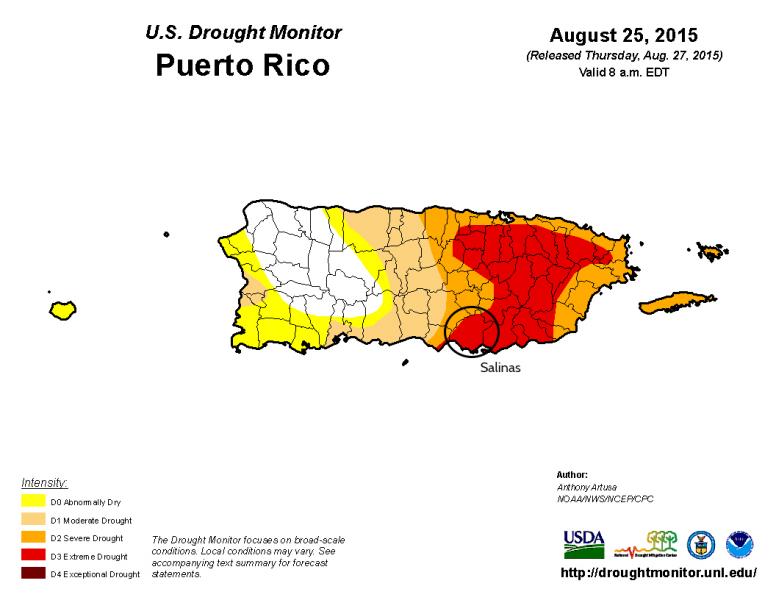

In 2015, Puerto Rico had been dealing with severe drought for over a year. Leading up to the drought, portions of the island experienced several consecutive years of below-normal rainfall, and the impacts were widespread. "All communities around the island were affected—millions of people," says Alejandro de la Campa, Director of the Caribbean Area Division of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

To add insult to injury, water levels in the island's Southern Coast aquifer had been steadily declining for 20 years. During successive dry years, water levels in the Salinas aquifer decline rapidly due to the imbalance caused by limited recharge and high rates of water extraction from wells. By 2016, the water level had dropped to 31.4 feet below land surface, the lowest of record. Because the Salinas aquifer is connected to the ocean, low water levels in the aquifer allow salt water from the ocean to gradually move inland and contaminate wells—the total dissolved salt concentration in drinking water wells has been rising since 2013, and has now reached the recommended upper limit for drinking water. The aquifer has also suffered from nitrate contamination from sources such as fertilizers and septic tanks.

Salinas is home to around 31,000 residents, several industries, irrigated farms, schools, hospitals, and the Camp Santiago National Guard training base—and all the people, buildings, and businesses depend exclusively on the aquifer for their water supply. Local leadership’s immediate response to the drought was to enforce a municipal water ration by turning off well pumps for several hours each day. "There were rationing plans in place across the island. Many families [were] without water for two or three days," adds de la Campa.

The drought and resulting water rationing impacted residents, farmers, schools, and the local economy. No new wells were allowed, and no new connections to the town’s water supply were permitted. This eliminated any economic development activities that would require new water connections or wells. Scientists at the nearby Jobos Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve noted negative impacts to ecosystems, including die-offs of blue land crabs and native trees. Michael Vega, a local papaya farmer, said flatly: "If we don't get a solution for this, we'll probably have to go to do something else. There's no future in agriculture without a fix of the problem."

The Salinas community was in crisis. Even with the rationing, they needed a long-term solution. The Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DNER) declared a water emergency until a remedy could be implemented.

An expert solution: Aquifer storage and recharge

A 2015 Executive Order issued by former Governor Alejandro García Padilla led to the formation of an interagency committee to address the water crisis and protect aquifers in the southern region. The committee, led by DNER, discussed several alternatives, including reducing water supplies to agricultural users in order to supply a new water filtration plant, construction of a new pipeline to transport water from a distant area, and desalination. After consideration, they decided that none of these options would be a good fit for Salinas—all were expensive, and the first two would reduce water supplies available to other users.

But another plan to divert water from other locations and store it in the aquifer—a strategy called aquifer storage and recovery—was deemed feasible. The strategy would work by harvesting some of the water from the nearby Patillas Reservoir that normally spills into the sea. A canal system would transport the water to the Salinas area, where it would be used to recharge and restore the aquifer. Analyses showed that aquifer storage and recovery would be much less costly than the other alternatives they considered; the strategy could also enhance water availability for agriculture and other users in addition to maintaining the existing municipal supply.

Once this course of action was agreed upon, officials in Salinas got to work identifying potential funding sources. They applied for and were awarded a FEMA Pre-Disaster Mitigation (PDM) grant to subsidize what was to become the Aquifer Storage and Recovery (ASR) mitigation project. These grants are available to assist states, U.S. territories, federally recognized tribes, and local communities in implementing sustainable mitigation projects that reduce their risks to future hazard events. Because reduced risks translate to reduced reliance on federal recovery funding, these grants provide the majority of funds for project costs, and grantees contribute a smaller portion. In the case of the ASR project, the government of Puerto Rico is providing $714,053 and FEMA has awarded the remaining project costs of $2,142,159—money was released to fund the project in August 2017.

Providing motivation and a model

Once the project is in operation, the average recharge volume is expected to provide the aquifer with twice as much water as is currently withdrawn by Salinas for municipal supply—supporting resuscitation of the local economy and community development. "We want to have everybody involved in this," says Sonny Beauchamp, a Mitigation Specialist with FEMA's Caribbean Area Division. "I think that by having this committee in place, we will be able to not only accomplish the project as it is, but also motivate other communities in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to pursue projects of this nature."

Alejandro de la Campa, FEMA's Caribbean Area Division Director, explains: "This is a unique mitigation project in the municipality of Salinas, and that's why we feel so proud of sponsoring this mitigation project. We know that it will serve also as an example to other communities in Puerto Rico, and at the same time to other communities in the entire United States."

To learn more about FEMA's hazard mitigation assistance program, visit the program website.