Heavy rain

Prolonged heavy rains over south central Wisconsin in June 2008 did not particularly concern Reedsburg Public Works Director Steve Zibell. After all, just two years earlier the city had completed an $11 million upgrade to their wastewater treatment plant, including construction of a new berm along the Baraboo River to protect the plant from a 100-year flood. However, after two weeks of wet weather, a whopping 14 inches of rain had fallen across the area, and river levels rose two feet higher than the new berm. The new treatment plant was inundated and inoperable for weeks, discharging raw sewage into the Baraboo River.

After spending $850,000 in repairs, plus $400,000 to raise the berm an additional three feet, Zibell feels that Reedsburg is ready for the next big storm event. But across the country, communities learning of what happened at Reedsburg wondered, “How would a storm like that impact our community?”

More heavy rains

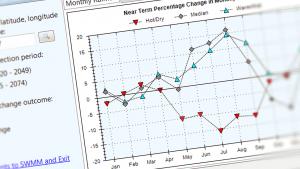

The historical record of rainfall and projections of future rainfall from climate models both paint a picture of heavier and more frequent extreme storms for Wisconsin in the future. However, the potential for flooding—identified through mapping of areas anticipated to experience flooding once or more per century—is calculated from historical records that don’t reflect today’s changing climate conditions. Combined with the typical municipal approach of adapting to rainfall impacts after a large storm has occurred, many communities are vulnerable to extreme rainfall events.

Concerns in Madison

Just south of the Baraboo River watershed, Madison—Wisconsin’s state capitol—is in the Yahara River watershed. The most obvious feature of the Yahara watershed is a slow-draining chain of lakes that runs through a mixed urban and agricultural landscape. A portion of Madison is on low-lying land between two of the lakes; in fact, no place in the city is far from a lake. Runoff from expanding urban development is already causing erosion of wetlands and shorelines, so residents have some awareness of flooding issues. Several communities in the region recognized they were ill-prepared for the flooding that would occur if they experienced extreme rainfall.

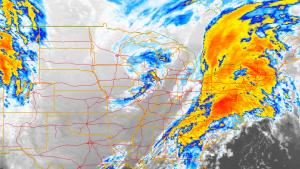

Simulating extreme precipitation

NOAA’s Sectoral Applications Research Program provided funding to scientists at the University of Wisconsin-Madison to build a tool that would allow communities to assess their vulnerability to extreme rainfall without needing to experience it. Using NOAA’s NEXRAD rainfall radar record of the 2008 Baraboo River storm, they built a computer simulation to “transpose” the 2008 rainfall over the Yahara River watershed, and model the runoff, streamflows, and lake levels as if the storm had occurred further south than its actual location. Using this approach, the model helped planners discover unforeseen vulnerabilities and adaptation opportunities. The simulated storm helped municipalities and businesses recognize steps they could take to minimize the impacts of future extreme storms.

Simulation Results

What would happen if the 2008 storm had occurred over the Yahara watershed?

- Overland flows and urban runoff would swell streams to new heights.

- Lake Mendota would overflow its banks, closing the regional airport.

- The City of Madison would be split in half by floodwaters that could remain standing for as long as ten days.

How are local governments in the Yahara River watershed preparing for extreme rainfall?

- Evaluating the ability to detain water in natural depressions upstream from Madison.

- Improving monitoring of rainfall and stream flows.

- Updating Lake Mendota water level management scenarios to increase downstream discharges prior to heavy rainfall.

- Budgeting for more sandbags and emergency response capacity.

- Identifying infrastructure at greater risk of flooding.

- Discussing new controls on stormwater runoff from urbanized areas.

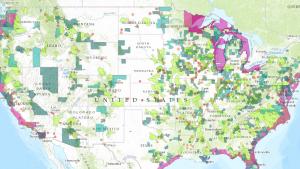

Transposing virtual storms to new locations

Building on this storm transposition simulation, communities can now use NOAA NEXRAD rainfall data from any recent rainfall event to demonstrate what would happen if the event occurred in their location. Understanding how a storm that happened nearby would impact their own location identifies vulnerabilities and helps communities see options for how they can build resilience.

Using the storm transposition tools requires specific technical skills. Ultimately, the developers envision the tool as a NOAA/USGS product, available online with either a catalog of design storms or the ability to choose specific storm events from the NEXRAD archives. Currently, however, the tools are used primarily by engineering consultants or regional planning commission staff.

Editor's note: In September 2017, we learned that the Principal Investigators of this project have retired. Documentation of their efforts is available on this page. We would love to hear from anyone who takes steps to make storm transposition possible for other communities.

References

- Fitzpatrick, F.A., M.C. Peppler, J.F. Walker, W.J. Rose, R.J. Waschbusch, and J.L. Kennedy, 2008: Flood of June 2008 in Southern Wisconsin. U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2008–5235, 24 pp.

- Potter, K., Demonstration Storms for Identifying Climate Vulnerability (presentation). NOAA Climate Program Office "Working with Communities" webinar, February 21, 2014, 24 pp.

- Vavrus, S.J., and R. Behnke, 2014: A comparison of projected future precipitation in Wisconsin using global and downscaled climate model simulations: Implications for public health. Int. J. Climatol., 34, 3106–3124, doi:10.1002/joc.3897.

- Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts, 2011: Wisconsin’s Changing Climate: Impacts and Adaptation. Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, 226 pp.